10 The Great Church Divide

Unpacking the Bethel Baptist Split and Its Impact on Jacksonville

Ken Green

Jacksonville, Florida is a city rich in culture and history. With its modern architecture, devoted sports fans, and a population of over one million people, it is truly a place to behold. However, deep behind Jacksonville’s aesthetic and look is a city with a broken past—small shards of stories within its archives that have yet to be fully pieced together and brought into the light. One such story took place some thirty-three years after the Civil War: the 1868 division of Bethel Baptist Church into two racially distinct congregations. The split led to the two churches becoming the oldest historical “Black” and oldest historical “White” churches in Jacksonville. One explanation for the lack of knowledge about the split is likely related to the city fire in 1901 that destroyed much of Jacksonville’s historical records. This essay tries to piece this history back together. It interprets the split as a microcosm of Jacksonville residents’ beliefs about race and Reconstruction and as a prelude to the Jim Crow era.

The story of Bethel Baptist Church goes back to July 1838, when Rev. James MacDonald, a Scottish immigrant who came to America in 1818 at the age of 20, and Rev. Ryan Frier, a state missionary, began holding the first church meetings at “Mother Sam’s”, a local plantation. Aside from the two co-pastors, the congregation consisted of Rev. MacDonald’s wife and Mr. and Mrs. Elias G. Jaudon, Mr. Jaudon would become the church’s first deacon, and two slaves, Peggy (female) and Bauchus (male), would be the church’s first members. Two years after the first services in 1838, a designated meeting house was erected on Duval and Newman streets. One year later, on February 10, 1841, Bethel would be incorporated by the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida. The first church building would eventually be sold to Presbyterians or Methodists (this is not completely clear) in 1844, but a lot was purchased by Deacon Jaudon in the west Lavilla neighborhood on Church Street between Hogan and Julia and then given to the church. On this lot, a new and more permanent meeting house would be erected in 1861, with the desire for it to be in a more central location.

1861 was a monumental year for Bethel Baptist Church, Jacksonville, and the nation. The beginning of the Civil War deepened cleavages between the city’s Northern and Southern-born residents and resulted in four different occupations by Federal forces between 1862 and 1865 that weakened the institution of slavery in Northeast Florida.

Though the story of the Civil War and Jacksonville runs deep, the direct impact that the war had on Bethel runs even deeper. In the South during the war, many churches were used as hospital facilities for soldiers on both sides of the war. Bethel was one of those churches. On the day of the Battle of Olustee, February 20, 1864, the church was taken possession of by the Federal officers and used as a hospital for wounded soldiers. From this time on, until the troops left Jacksonville in the summer of 1866, the church was occupied as a military hospital by the Federal army. The building was greatly damaged. According to an eyewitness account published in the Baptist annual: “The church was left in deplorable condition when vacated by the United States troops. Scarcely a pane of glass was left in the windows, and very little plastering on the walls.” The church and the city’s social order needed reconstruction. Slavery had been abolished, and African Americans were given access to freedoms many of them would never have thought they would see. Newly emancipated Black people rapidly grasped the connection between economic justice and electoral politics. African Americans believed that access to inexpensive farmland, the right to bargain with employers, free public schools, and the elective franchise were the keys to liberty. A Black Floridian testified in 1867 that “[freed people] are all seeking lands for themselves and building houses to live in. Some have been fortunate enough to make five or ten bales of cotton and many bushels of corn…We are all looking for the day when we shall vote, to sustain the great Republican Party.” African Americans were primed and ready to make a lasting change in the city they called home.

Shortly after the war ended, the congregation began to reassemble and repair the damaged church. At that time, the membership was composed of 40 White members and 240 Black members. During this time, the congregation had a dispute over who owned the church’s name and property. It is unclear who instigated the dispute, as both sides have conflicting stories. All that is fully known is that an effort was made to separate the White and Black members of the congregation. Because the dispute could not be handled internally, the issue was brought to court before a judge who made a ruling that the Black members of the church were the rightful owners and had all rights to the church building and name, as they were in the overwhelming majority. A short while after, the Black members finally accepted an offer of $400 for their interest in the property, withdrew, and built for themselves a new church, which they first called “First Baptist Church” and then Bethel Baptist Church, taking the original name. The church building was erected on the northwest corner of Main and Union streets. The church of the White congregation would be renamed Tabernacle Baptist and then First Baptist Church in 1892.

The desire for separate churches grew among Florida Negro Baptists until it came to be expressed in the formation of their churches. Several factors explain the growing sense of need among Black Baptists for separate churches. First, it quickly became apparent that although many White Baptists were genuinely concerned for their spiritual and moral welfare, they were not willing to give Blacks full freedom and equality in the life of the denomination. Second, even if they had been given full equality in the churches, Black Baptists could not feel completely free. As they were in the same churches as their masters, they felt psychologically dependent. Thus, at the first opportunity many Black Baptists moved to establish their separate churches. This perspective is central to understanding the emotional significance of the church separation among newly freed African Americans. The feeling that even though I am legally free, my freedom is tainted by the thoughts of being in the same house of worship as the people whom I, for so long, desired to be free from. This is a feeling that, though nowadays may be seen as cynical, is an understandable sentiment that we must respect.

After the split, both Bethel Baptist and Tabernacle (soon to be First Baptist) would choose new leadership. Bethel would choose former slave Cataline B. Simmons as their pastor. Simmons was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1806. His owner moved to Florida and enslaved Simmons until the close of the Civil War. In 1870, shortly after being elected as Bethel’s first African American pastor, Simmons was elected to become a member of the Jacksonville City Council, becoming one of the first two African Americans to serve on the council. Rev. Simmons would serve Bethel Baptist for twelve years, from 1868 to 1880. First Baptist’s pastor after the split in 1868 was Rev. M.M. Wamboldt. In 1900, First Baptist would elect one of the longest-serving pastors, W.A. Hobson. Hobson would serve First Baptist for 23 years and would later have the Hobson Auditorium on church property named after him.

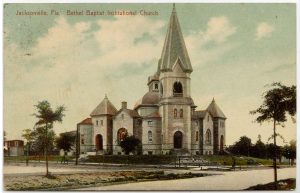

During the early years of church history, after the split, both Bethel and First Baptist would see growth and success. In 1895, Bethel would erect a brand-new building for itself, and the congregation would grow from tens to a few hundred. Bethel was also strongly connected with some of Jacksonville’s prominent African American figures. Clara White, a well-known humanitarian and social figure in Jacksonville, was one of the charter members of Bethel after the split. The Johnsons – James Weldon, John Rosamond, and their father James – were all connected to the church and the larger Black community in the city. John Rosamond Johnson was the organist and choir director at Bethel for three years, and James Johnson would go on to found and be the first settled pastor of Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church. J. Milton Waldron, Bethel’s elected pastor in 1892, would go on to be an integral part of African American and city politics as well as become a founding member of the Niagara Movement and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). First Baptist would also continue to grow in the years after the split, becoming an integral part of the Southern Baptist Convention while also being a leader in many aspects in downtown Jacksonville.

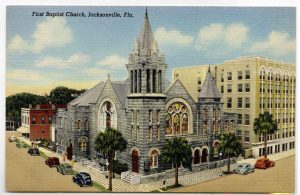

Despite their separate paths, both churches experienced sustained growth and increasing influence within the city’s community. However, on an unexpectedly windy spring day, a conflagration would consume Jacksonville. On May 3rd, 1901, the Great Fire destroyed 146 blocks, including both churches. The fire would not keep the city down for long, though, as only a short year later, buildings were already being erected to replace the ones that had been lost. Architect Henry John Klutho would be one of the significant reasons for this and would play a huge part in the rebuilding of First Baptist Church. Bethel would also soon erect a building that would serve as their permanent residence until renovations were made in the early 21st century.

Both churches would continue to have an impact on the city after the fire. Bethel would be a center for not just worship but education and social activities as well. For years, they would have multiple schools and graduating classes for business courses as well as others. They would also play a part in the founding of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company, which would work to help Black Americans obtain life insurance policies and mortgages until it ceased operations in 1990. First Baptist would see some economic trouble during the mid-20th century and would lose its educational building. However, under new leadership, their fortunes were reversed, and they were able to climb out of the troubles and regain their educational building. Now the church owns 10 blocks of land downtown and hosts about 3,000 people every Sunday. Bethel hosts an estimated 12,000.

The 1868 split between Bethel Baptist and First Baptist reflected and reinforced many racial divides within Reconstruction-era Jacksonville. However, despite the split, both churches became even greater pillars of the Jacksonville community. Bethel is a pillar of Black resilience, and First Baptist was once a religious and political force in the heart of Downtown. A lasting impact has been left on the entire city of Jacksonville, whether Black or White. The story of Bethel and First Baptist is more than just a church split, but it is an event that is a mirror of a city that is grappling with identity, freedom, and power in the wake of a war that shook up social norms. In their separate paths and areas, these churches have helped shape the very soul of Jacksonville, one divided past, but two enduring legacies.

Ken Green

Kendrall Green Jr. was born in Chicago, Illinois, and raised in the northwest Indiana and Chicagoland suburbs before moving to Jacksonville, Florida with his family four years ago. He is a recent high school graduate and earned his Associate of Arts degree through dual enrollment at Florida State College at Jacksonville, where he was part of the Honors Program and the President’s List. Kendrall is the second oldest of eight children in a family of ten. His writing is deeply influenced by his background in the Christian church and his interest in exploring lesser-known stories and mysteries within that context. For this paper, he conducted multiple hours of research and gathered factual historical data from across Jacksonville to create the most historically accurate account possible.

Bibliography

African American Registry. “Bethel Institutional Baptist Church Is Founded.” African American Registry. June 1, 2024. https://aaregistry.org/story/bethel-institutional-baptist-church-founded/.

Baptist Annual. Baptist Annual. Jacksonville Public Library, Downtown Campus, Florida, n.d.

Wall, Belton S. “In The Beginning.” Essay. In A Tale to Be Told: The History of the First Baptist Church of Downtown Jacksonville, n.d.

Bethel Baptist Church Archives. Bethel Baptist Church Archives. Jacksonville, Florida.

Canvas. Learning Unit 5, Sectionalism, Secession, and the Civil War in Jacksonville, 1840s to 1860s.

Crooks, James B. “The History of Jacksonville Race Relations. Part 1: Emancipation and Jim Crow.” The Florida Times-Union, September 21, 2021. https://www.jacksonville.com/story/opinion/columns/guest/2021/09/05/crooks-history-jacksonville-race-relations-emancipation-and-jim-crow/8210815002/.

Davis, T. Frederick. History of Jacksonville, Florida and Vicinity. St. Augustine, Florida: The Florida Historical Society, 1925.

Florida State Library and Archives. “First Baptist Church, Jacksonville.” Florida Memory. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/247922/.

Joiner, Edward Earl. A History of Florida Baptists. Jacksonville, Florida: The Florida Baptist Convention, 1972.

Legacy (Florida Baptist Historical Society) 12, no. 8 (August 20): 2.

National Park Service. “Bethel Baptist Institutional Church (Jacksonville, Florida).” National Park Service. Last updated January 26, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/bethel-baptist-institutional-church-jacksonville-florida.htm.

Ortiz, Paul. Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

The Daily Florida Union. March 31, 1877.

The Florida Times-Union. July 14, 1883, 4. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.