14 A Ride through Time in Empire Point

Clay Zeigler

I went to the Episcopal School of Jacksonville before it was fancy. I got there not in a silver Tesla, but on a green Raleigh. My three-speed and I made the commute more than 1,500 times over nearly five years. So, after every road patch and sidewalk crack had been committed to memory, there was plenty of time for looking around and wondering: Why were a few of these buildings so much older than the rest? Who built them and what did they used to be? What did this whole place used to be?

The axis of my teenage world was Empire Point, a subdivision of about 150 mostly ranch-style houses tucked off Atlantic Boulevard just east of the Hart Bridge in Jacksonville’s St. Nicholas area. One of those houses was built by my parents. We moved there in 1976, gleefully leaving behind the nice-enough apartment complex just across the creek. The new housing was much bigger; and the ride to Episcopal seemed shorter.

Every day on River Point Road, I passed a monstrous tan house that looked like it belonged to the Addams Family. People said the owners were the Trout family, and their swimming pool, situated strangely in the front yard and close to the road, was said to be the oldest in the county. That seemed plausible, given the pool’s stone benches, antique lanterns, and the deep-green color of its stagnant water. I heard the Trouts had a wine cellar where they threw big Halloween parties. Another big house was white and didn’t even face the street. But from a friend’s house I saw its six square, two-story columns and endless lawn. The place looked like it could have been in a Civil War movie.

My ride to school ended at The Yellow House, where I had been told to lock up my bike for the day. The curiously old cottage had fancier columns, and its porches ran across the front and all the way down the side. Just across St. Elmo Drive was an old shed that was strangely long and had a pointed turret at one end. This is where we would gather to be handed the watered-down Gatorade that helped most of us survive summer-football two-a-days. And over by the river was another old house where we took Art classes. This one had round columns and wide porches on three sides. The rooms were small, and the ceilings were low. They called it The Acosta House. No one said why.

Empire Point, the Episcopal campus and the Colonial Point complex were all part of the 385 acres granted by the Spanish government to Reuben Hogans in 1808. (See Note 1.) His brother got from the Spanish 605 acres across the river that would one day become downtown Jacksonville. Reuben’s land ran along the St. Johns River from Miller Creek to Little Pottsburg Creek (Davis).

Hazzard’s Bluff

The Reuben Hogans grant was a small slice of the 10,000 acres acquired in 1769 by London merchant Edward Wood and conveyed soon after to the Second Earl of Egmont. It extended from Miller Creek to present-day University Boulevard and upriver to a spot in present-day San Jose. It was named Cecilton Plantation by the earl’s agent, Stephen Egan. In 1776, after rebels from Georgia destroyed the earl’s plantation on Amelia Island, Egan led his family and a hundred enslaved people to Cecilton, which Egan grew into a producer of naval stores. Upon the earl’s death in 1785, the enslaved were shipped away. The earl’s widow was sent an accounting showing that in the first three months of 1785, Egan’s sales of lumber and naval stores had netted a profit of 708 pounds Sterling (“British Farms and Plantations on the St. Johns River”). That quarterly profit would be worth nearly $175,000 today.

In the 1820s, the land along what was known as Hazzard’s Bluff was passed from Francis Richard II to John Sammis, the son-in-law of Zephaniah Kinsgley. (See Note 2.) In the decade leading up to the Civil War, Sammis sold off the property for three sawmills in the area. All three were burned during the Civil War. Only one was rebuilt – the Empire Mill (Wood 306). Erected by John Clark in 1850, it was the first circular steam sawmill in Florida (Wood 312). The Empire Mill was located on the point of land overlooking where the St. Johns flows into what we call the Arlington River (Ken Durkee interview).

In July 1864, Brigadier General William Birney devised a plan to rebuild the Empire Mill. He would steam up the Nassau River with a force of infantry, capture the Holmes Saw Mill from the Confederates, dismantle it, and reassemble it along the St. Johns. The plan was part of a larger one to end the threat of Confederate mines in the river that had in recent months sunk the Federal transport Maple Leaf and two other ships. The Alice Price was a sidewheeler 151 feet long. Loaded with men and the captured machinery, the ship struck a mine 8 miles from Jacksonville. The explosion breached the hull in three places. The Alice Price was the last of the four ships lost in the St. Johns to Confederate mines (Schafer 215-216).

Marabanong

Before the Civil War, a physician named Thomas Perley had built a home on Hazzard’s Bluff not far from the Empire Mill. A wine cellar with a brick facade was built right into the bluff. The doctor sold his Perley Place to a local banker, D.G. Ambler, who sold it in 1870 to an astronomer from England, Thomas Basnett. When Perley Place burned down, Basnett replaced it in about 1876 with a 6,000-square-foot Queen Anne-style mansion with wraparound porches on both floors and an octagonal tower in front. There are 21 rooms, 121 windows and seemingly countless turned posts and spindles. The origin of its name, Marabanong, is a matter of debate. Some say it’s the word for paradise in the language of New Zealand’s native Māori people. Others have their doubts (Wood 314).

Basnett shared Marabanong with his wife, a scientist from New York named Eliza Wilbur. The first woman to lecture science students at Harvard University, she patented inventions including a large astronomical telescope. When Basnett died, Eliza married Mathieu Souvielle, a French physician who specialized in the throat and lungs. By 1903, Marabanong was being touted in newspaper advertisements as an “international resort for tourists and invalids who require special attention.” After her second husband died in 1914, Wilbur sold her house to her cousin Grace Wilbur, who was known more formerly as Mrs. George W. Trout. She was involved nationally in the women’s suffrage movement; she published a novel; and she and her husband maintained a private zoo that included deer, various birds, and crocodiles (Wood 314). She added the swimming pool in 1921 (Soergel).

“Mrs. Souvielle was a suffragette and a very interesting lady,” Nellie Richards said in a 1980 newspaper article. “She had watched the buzzards fly and, accordingly, built an airplane. I used to go climb all over the plane, but I never knew if she ever tried to fly it.” Richards also recalled sitting on the riverbank as a child and watching the Great Fire of 1901. (See Note 3.) She remembered the Kalem Company filming at her church and even making a few quick bucks being an extra in a crowd scene (Rider, “Region Mapped in 1565”).

Thomas Wilbur Trout Jr., born in 1927, grew up at Marabanong, graduated from Landon High School, enlisted in the Navy at 18, got a degree, and, in 1962, went into business as a general contractor. (Dignity Memorial) Tom’s father had died when he was 14 and much of the land around Marabanong was sold off, but the Trout family held on to the house until 1983 (Woods).

Tom Trout made a unique contribution to Jacksonville. His offices were along Interstate 95 just north of Bowden Road, so to save money on advertising, Trout decided in the 1980s to put a billboard on his roof in plain view of the tens of thousands of passing motorists. On top was his trout logo and on the bottom was a message in black letters that changed twice a week – for decades. (Woods)

“The messages that came from a variety of sources,” wrote Florida Times-Union columnist Mark Woods, “had recurring themes. Character, empathy, faith, humor. ‘Horsepower was much safer when only horses had it.’ ‘Forbidden fruit is responsible for many bad jams.’ ‘If you want to leave footprints in the sands of time, wear work boots.’”

Since 1992, Marabanong has belonged to Joseph and Diantha Ripley, who bought it at auction for $165,000. Listed for sale in 2017 for nearly $1.5 million, it remains theirs. (Soergel)

Diven and the Durkees

The same year that Marabanong went up – 1876 – a Jacksonville Unionist named Paran Moody sold land nearby to Alexander S. Diven, who had been a general in the Union army and a Congressman from New York. The house Diven built in 1877 was described in 1885 as “one of the most beautiful in St. Nicholas. It contains 34 acres, and the mansion, a fine large house surrounded by a broad piazza, is distant from the landing some 200 yards.” Diven built an irrigation system and planted some 700 orange trees (Wood 312).

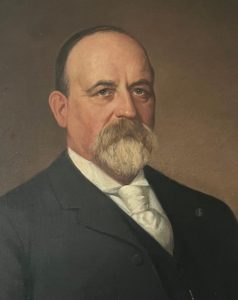

After Diven died in New York in 1896, his son sold the property to Dr. Jay Harvey Durkee (Wood 312; Diven’s death date and place from findagrave.com). Dr. Durkee’s father, Joseph Harvey Durkee, had been a captain in the Army and served with the general. (Ken Durkee interview)

A Durkee family history written in 1995 says, “In May 1863 at the battle of Chancellorsville, Joseph was severely wounded and taken prisoner. While a prisoner, his left arm was amputated by Dr. Todd, a brother of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of the president. Shortly after this he was returned to the north in a prisoner exchange. In spite of his handicap, he returned to action and served until the end of the war. He was on duty the night of President Lincoln’s assassination and was the person who carried the news to the War Department. He was appointed one of the bodyguards to escort the president’s body to Springfield, Illinois, and for this he received a gold medal from Congress. In December 1865 Joseph was sent to Florida to act as a disbursing officer and superintendent of schools under the Freedmen’s Bureau. In January 1868 he resigned from the Army and decided to remain in Florida, which he had come to love” (The Durkee Family Newsletter, 53-55).

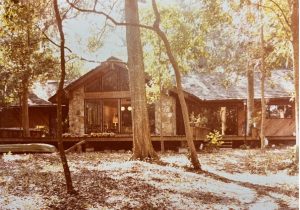

In addition to Empire Point, Dr. Jay Harvey Durkee acquired several Bay Street warehouses and land near the downtown train terminal that would one day become the Durkeeville neighborhood. The Empire Point house was a summer place, but Dr. Durkee liked it so much that eventually his family didn’t leave for downtown until after Thanksgiving. Dr. Durkee died in 1936 (The Durkee Family Newsletter, 64).

It was Dr. Durkee’s older son, a second Joseph Harvey Durkee, who in 1952 started to turn the family place into a subdivision. Born in 1906, Joe Durkee studied aerodynamics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While there he contracted polio and afterward walked using two canes. For 33 years he worked at First Federal Savings and Loan Association, retiring in 1972 as senior vice president (The Durkee Family Newsletter, 68-69).

“Dad and the kids made this a subdivision because of the [property] taxes,” explained Ken Durkee, admitting that by today’s standards they were low. We chatted in the living room of the 1877 house with Captain Durkee staring down from a portrait above the fireplace. “He had 40 acres; and he needed a hundred,” Ken said of his father, who bought the adjacent marsh, walled it off with limestone, and drained it. Today, dozens of houses sit all along River Basin Drive.

From working in the savings and loan industry, his father knew how to gauge people and their fitness to be his neighbors, Ken Durkee said. And he had some conditions: Houses had to be more than 2,000 square feet. The garage couldn’t face the street. And he had to approve the house plans. I remember my parents talking about having to appear before Joe Durkee and their relief when he approved their plans for Lot 9, which they had purchased for $33,000 from the Margaret Durkee McCarthy Trust. Joe Durkee himself acknowledged his demands in an interview for a 1980 newspaper article.

“A lot of people thought I was a son-of-a-gun,” he told The Florida Times-Union. “I was very particular about who bought the property. I wanted permanent residents, not people who were constantly changing. Also, I wanted buyers to build immediately, so I offered a 10 percent discount if they started houses within 60 days” (Rider, “Empire Point”).

The story notes that, “Many changes have taken place since Empire Point was first planned in 1952. Atlantic Boulevard has been widened to six lanes, and the Hart Bridge was opened in 1967. … Then, to the dismay of Empire Point residents, the Catholic Diocese sold 13.5 acres of land from the basin to Little Pottsburg Creek to a developer for a $5.8 million, 302-unit apartment complex. The first units of Colonial Point opened in 1969” (Rider, “Empire Point”).

Reading this in 2024 made something click. It explains why I was told as a boy that Paul Tanner, the bishop of St. Augustine from 1968 to 1979, lived in the house on a sliver of land between the apartment complex and the subdivision. That house has long been in private hands, according to county records available online that don’t extend back to the years the diocese was said to own the property. They do show the house at 5051 Atlantic Boulevard was built in 1970, during Tanner’s tenure. Two people from the Diocese of St. Augustine said by email that someone else would try to answer my questions.

Keystone Bluff

As Empire Point was coming together in the 1960s, a school was being planned just up the river.

That story begins in 1881, when a section of Hazzard’s Bluff was purchased by Pennsylvanian Asa Packer, who built the Lehigh Valley Railroad and founded Lehigh University. His son had wanted the 30 acres here for hunting, but he died just three years after the purchase. So, it was Asa Packer’s daughter, Mary Packer Cummings, who arrived for a winter visit aboard her new 60-foot steam yacht. The boat and the land were called Keystone in honor of Pennsylvania, the Keystone State (Wood 312).

Like other wealthy winter visitors, Cummings and her husband commenced to build an estate. There was a 12-room house completed in 1890, stables, laundry, boathouse, and a well-fed swimming pool. Orange groves were planted. Then, in 1893, work was completed on a two-story guest cottage set on the bluff near the main house (Wood 312). It had been moved by the time I parked my bike there, but this was the Yellow House.

Charles Cummings often quarreled with his wife and their neighbors. After one argument, Cummings built a bowling alley 4 feet from his property line so his neighbor “would get the full benefit of the noise from the bowling … and the card games, which sometimes were quite hilarious and lasted far into the night” (Wood 313). This was the shed where we would gather for Gatorade. It had been moved and shortened, but this was the bowling alley.

L.H. Armstrong, the winter neighbor who inspired the Cummings bowling alley, built a two-story cottage in 1885. A boy who pilfered oranges from Armstrong’s groves was St. Elmo W. “Chic” Acosta, who bought the house in 1911, a year after he was elected to the city council. It was Acosta who added the Tuscan columns and the wraparound veranda where graduations are held now. When the St. Johns River Bridge opened in 1921, Acosta was able to live on the bluff year-round (Wood 313). That bridge is now the Acosta Bridge; and this was the Acosta House.

Keystone Bluff was willed to St. Johns Episcopal Parish when Mary Packer Cummings died in 1912; and for more than 30 years the diocese ran a children’s home there (Wood 312). Then in 1965 a court ruled that the intent of Cummings’ will allowed for the property’s use as a school. A Committee of 100 who had been planning that school bought the 12-acre Acosta property in 1967. (Construction of the new Hart Expressway had carved more than 4 acres off the end of their Cummings land.) With annual tuition set at $815, Jacksonville Episcopal High School opened in the fall of 1967 under its first headmaster, a Harvard man named Horton Reed (Episcopal School of Jacksonville, 14-24).

Reed and his family lived in Empire Point.

A walk with Ken

Even at 79, Ken Durkee still loves to fly. He had been in the air the morning we met to talk under that portrait of his great-grandfather, in a living room that seems frozen in time.

He hands me a piece of rusted metal – a manufacturer’s label, he’s been told, from a Hayes Fire Truck ruined in the Great Fire of 1901 and pushed into the river below his house as trash.

In the yard, under those six square columns and a canopy of mossy oaks, he points to a row of magnolias in a neighbor’s yard. He says they used to line a road that ran to his house from the river below. It takes a few seconds to imagine it.

It’s like so much of the history in Jacksonville: You can see it, but you have to look.

Notes

- There is a small neighborhood not explored in this essay, as it was not significant to me in my youth. The Live Oak Manor neighborhood has three streets and lies between Empire Point and the Episcopal campus. A house there is of historic significance. The Judge R.B. Van Valkenburg residence at 1231 Glengarry Road dates to about 1872, writes Wayne Wood in Jacksonville’s Architectural Heritage: Landmarks for the Future. Robert Bruce Van Valkenburg commanded U.S. troops at the Battle of Antietam and served as minister to Japan from 1866 until 1869, according to Wood. Van Valkenburg bought 18 acres on Hazzard’s Bluff in 1871, Wood says, making him the first of the wealthy New Yorkers to settle in Empire Point.

- Zephaniah Kinsgley (1765-1843) was the plantation owner, ship master and slave trader whose Northeast Florida properties included the Kingsley Plantation on Fort George Island.

- The Great Fire of 1901, one of the most destructive urban fires in U.S. history, burned much of Jacksonville on May 3, 1901.

Clay Zeigler

Clay Zeigler has worked as a writer and editor at three Florida newspapers and The Dallas Morning News in Texas. He retired in 2018 as managing editor of The Florida Times-Union and now devotes his time to volunteerism, travel, and learning. He remains active in the sport of rowing, which he learned on the St. Johns River nearly 50 years ago. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Clay lives with his wife in Riverside. With Wayne Wood, Clay wrote Fifty Strides Forward: Contributions of Riverside Avondale Preservation in its First 50 Years.

Works Cited

“British Farms and Plantations on the St. Johns River, 1763-1784,” Florida History Online, University of North Florida, Daniel L. Schafer, project director, 2019.

Davis, Ennis. “Neighborhoods: Empire Point,” Metro Jacksonville, May 1, 2013.

Durkee, Ken. Interviewed at the Durkee residence, Oct. 31, 2024.

Episcopal School of Jacksonville: True to the Dream, Grandin Hood Publishers, 2015.

https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/jacksonville-fl/thomas-trout-11148602

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5995034/alexander-samuel-diven

https://paopropertysearch.coj.net/Basic/Search.aspx

Rider, Wini. “Empire Point: Proximity to town blends with countrystyle living,” The Florida Times-Union, January 14, 1980.

Rider, Wini. “Region mapped in 1565,” The Florida Times-Union, January 14, 1980.

Schafer, Daniel L. Thunder on the River: The Civil War in Northeast Florida, University Press of Florida, 2010.

Soergel, Matt. “Marabanong, a colorful Victorian mansion in Jacksonville, is now for sale,” The Florida Times-Union, April 19, 2017.

The Durkee Family Newsletter, Volume XIV, No. 3, Fall 1995, supplied by Ken Durkee.

Wood, Wayne W. Jacksonville’s Architectural Heritage: Landmarks for the Future, Bicentennial Edition, Jacksonville Historical Society, 2022.

Woods, Mark. “Tom Trout, the man behind I-95 billboard, dies – but messages will continue,” The Florida Times-Union, February 19, 2023.