25 Nutrition

Nutritional needs change with age. Let’s examine how caregivers should nourish children during the first years of life and some risks to nutrition that they should be aware of.

Breastfeeding

Breast milk is considered the ideal diet for newborns. Colostrum, the first breast milk produced during pregnancy and just after birth has been described as “liquid gold” (United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), 2011). It is very rich in nutrients and antibodies. Breast milk changes by the third to fifth day after birth, becoming much thinner, but containing just the right amount of fat, sugar, water and proteins to support overall physical and neurological development. For most babies, breast milk is also easier to digest than formula. Formula fed infants experience more diarrhea and upset stomachs. The absence of antibodies in formula often results in a higher rate of ear infections and respiratory infections. Children who are breastfed have lower rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a lower risk of SIDS. The USDHHS recommends that mothers breastfeed their infants until at least 6 months of age and that breast milk be used in the diet throughout the first year or two.

Maternal Benefits of Breastfeeding

Several recent studies have reported that it is not just babies that benefit from breastfeeding. Breastfeeding stimulates contractions in the mother’s uterus to help it regain its normal size, and women who breastfeed are more likely to space their pregnancies further apart. Mothers who breastfeed are at lower risk of developing breast cancer (Islami et al., 2015), especially among higher risk racial and ethnic groups (Islami et al., 2015; Redondo et al., 2012). Women who breastfeed have lower rates of ovarian cancer (Titus-Ernstoff, Rees, Terry, & Cramer, 2010), reduced risk for developing Type 2 diabetes (Schwarz et al., 2010; Gunderson, et al., 2015), and rheumatoid arthritis (Karlson, Mandl, Hankinson, & Grodstein, 2004). In most studies these benefits have been seen in women who breastfeed longer than 6 months.

Challenges to Breastfeeding

However, most mothers who breastfeed in the United States stop breastfeeding at about 6-8 weeks, often in order to return to work outside the home (USDHHS, 2011). Mothers can certainly continue to provide breast milk to their babies by expressing and freezing the milk to be bottle-fed at a later time or by being available to their infants at feeding time. However, some mothers find that after the initial encouragement they receive in the hospital to breastfeed, the outside world is less supportive of such efforts. Some workplaces support breastfeeding mothers by providing flexible schedules and welcoming infants, but many do not. In addition, not all women may be able to breastfeed. Women with HIV are routinely discouraged from breastfeeding as the infection may pass to the infant. Similarly, women who are taking certain medications or undergoing radiation treatment may be told not to breastfeed (USDHHS, 2011).

Cost of Breastfeeding

In addition to the nutritional benefits of breastfeeding, breast milk does not have to be purchased. Anyone who has priced formula recently can appreciate this added incentive to breastfeeding. Prices for a year’s worth of formula and feeding supplies can cost well over $1,500 (USDHHS, 2011).

But there are also those who challenge the belief that breast milk is free. For breastmilk to be completely beneficial for infants the mother’s life choices will ultimately affect the quality of the nutrition an infant will receive. Let’s consider the nutritional intake of the mother.

Breastfeeding will both limit some food and drink choices as well as necessitate an increased intake of healthier options. A simple trip down the supermarket aisles will show you that nutritious and healthier options can be more expensive than some of the cheaper more processed options. A large variety of vegetable and fruits must be consumed, accompanied by the right proportions and amounts of the whole grains, dairy products, and fat food groups.

Additionally, it is also encouraged for breastfeeding mothers to take vitamins regularly. That raises the question of how free breastfeeding truly is.

A Historic Look at Breastfeeding

The use of wet nurses, or lactating women hired to nurse others’ infants, during the middle ages eventually declined and mothers increasingly breastfed their own infants in the late 1800s. In the early part of the 20th century, breastfeeding began to go through another decline. By the 1950s, it was practiced less frequently as formula began to be viewed as superior to breast milk.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, greater emphasis began to be placed on natural childbirth and breastfeeding and the benefits of breastfeeding were more widely publicized. Gradually rates of breastfeeding began to climb, particularly among middle-class educated mothers who received the strongest messages to breastfeed.

Today, women receive consultation from lactation specialists before being discharged from the hospital to ensure that they are informed of the benefits of breastfeeding and given support and encouragement to get their infants to get used to taking the breast. This does not always happen immediately and first time mothers, especially, can become upset or discouraged. In this case, lactation specialists and nursing staff can encourage the mother to keep trying until baby and mother are comfortable with the feeding.[1]

Alternatives to Breastfeeding

There are many reasons that mothers struggle to breastfeed or should not breastfeed, including: low milk supply, previous breast surgeries, illicit drug use, medications, infectious disease, and inverted nipples. Other mothers choose not to breastfeed. Some reasons for this include: lack of personal comfort with nursing, the time commitment of nursing, inadequate or unhealthy diet, and wanting more convenience and flexibility with who and when an infant can be fed. For these mothers and infants, formula is available. Besides breast milk, infant formula is the only other milk product that the medical community considers nutritionally acceptable for infants under the age of one year (as opposed to cow’s milk, goat’s milk, or follow-on formula). It can be used in addition to breastfeeding (supplementing) or as an alternative to breastmilk.

The most commonly used infant formulas contain purified cow’s milk whey and casein as a protein source, a blend of vegetable oils as a fat source, lactose as a carbohydrate source, a vitamin-mineral mix, and other ingredients depending on the manufacturer. In addition, there are infant formulas which use soybeans as a protein source in place of cow’s milk (mostly in the United States and Great Britain) and formulas which use protein hydrolysed into its component amino acids for infants who are allergic to other proteins.[2]

One early argument given to promote the practice of breastfeeding was that it promoted bonding and healthy emotional development for infants. However, this does not seem to be the case. Breastfed and bottle-fed infants adjust equally well emotionally (Ferguson & Woodward, 1999). This is good news for mothers who may be unable to breastfeed for a variety of reasons and for fathers who might feel left out.

When, What, and How to Introduce Solid Foods

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends children be introduced to foods other than breast milk or infant formula when they are about 6 months old. Every child is different. Here are some signs that show that an infant is ready for foods other than breast milk or infant formula:

- Child can sit with little or no support.

- Child has good head control.

- Child opens his or her mouth and leans forward when food is offered.

How Should Foods Be Introduced?

The American Academy of Pediatrics says that for most children, foods do not need to be given in a certain order. Children can begin eating solid foods at about 6 months old. By the time they are 7 or 8 months old, children can eat a variety of foods from different food groups. These foods include infant cereals, meat or other proteins, fruits, vegetables, grains, yogurts and cheeses, and more.

If feeding infant cereals, it is important to offer a variety of fortified infant cereals such as oat, barley, and multi-grain instead of only rice cereal. The Food and Drug Administration does not recommend only providing infant rice cereal because there is a risk for children to be exposed to arsenic.

Children should be allowed to try one food at a time at first and there should be 3 to 5 days before another food is introduced. This helps caregivers see if the child has any problems with that food, such as food allergies.

The eight most common allergenic foods are milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans. It is no longer recommended that caregivers delay introducing these foods to all children, but if there is a family history of food allergies, the child’s doctor or nurse should be consulted.[3]

It may take numerous attempts before a child gains a taste for it. So caregivers should not give up if a food is refused on first offering.

USDA Infant Meal Patterns

The United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service provides the following guidance for the day time feeding of infants and toddlers.

Infant Meal Patterns[4]

|

Meal |

0-5 months |

6-11 months |

|

Breakfast |

4-6 fluid ounces breastmilk or formula |

6-8 fluid ounces breastmilk or formula 0-4 tablespoons infant cereal, meat, fish, poultry, whole eggs, cooked dry beans or peas; or 0-2 ounces cheese; or 0-4 ounces (volume) cottage cheese; or 0-4 ounces yogurt; or a combination* 0-2 tablespoons vegetable, fruit, or both* |

|

Lunch or Supper |

4-6 fluid ounces breastmilk or formula |

6-8 fluid ounces breastmilk or formula 0-4 tablespoons infant cereal, meat, fish, poultry, whole eggs, cooked dry beans or peas; or 0-2 ounces cheese; or 0-4 ounces (volume) cottage cheese; or 0-4 ounces yogurt; or a combination* 0-2 tablespoons vegetable, fruit, or both* |

|

Snack |

4-6 fluid ounces breastmilk or formula |

2-4 fluid ounces breastmilk or formula 0-½ bread slice; or 0-2 crackers; or 0-4 tablespoons infant cereal or ready-to-eat cereal* 0-2 tablespoons vegetable, fruit, or both* |

*Required when infant is developmentally ready. All serving sizes are minimum quantities of the food components that are required to be served.

Meal Patterns for Children (1-2 years)[5]

|

Meal |

Ages 1-2 |

|

Breakfast |

½ cup milk ¼ cup vegetables, fruit, or both ½ ounce equivalent grains |

|

Lunch or Supper |

½ cup milk 1 ounce meat or meat alternative 1/8 cup vegetables 1/8 cup fruits ½ ounce equivalent of grains |

|

Snack |

Select two of the following: ½ cup of milk ½ ounce meat or meat alternative ½ cup vegetables ½ cup fruit ½ ounce equivalent of grains |

Note: All serving sizes are minimum quantities of the food components that are required to be served.

Child Malnutrition

There can be serious effects for children when there are deficiencies in their nutrition. Let’s explore a few types of nutritional concerns.

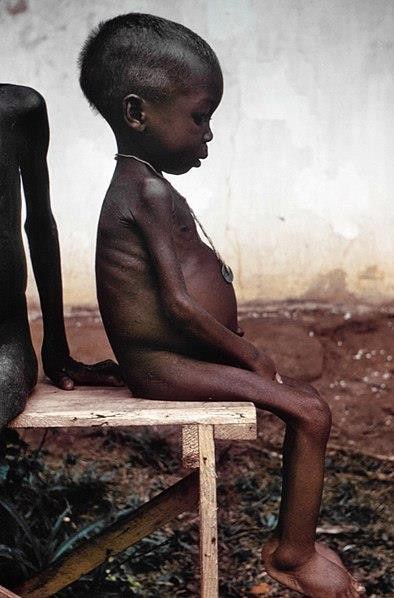

Wasting

Children in developing countries and countries experiencing the harsh conditions of war are at risk for two major types of malnutrition, also referred to as wasting. Infantile marasmus refers to starvation due to a lack of calories and protein. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition lose fat and muscle until their bodies can no longer function. Babies who are breastfed are much less at risk of malnutrition than those who are bottle-fed.

After weaning, children who have diets deficient in protein may experience kwashiorkor or the “disease of the displaced child,” often occurring after another child has been born and taken over breastfeeding. This results in a loss of appetite and swelling of the abdomen as the body begins to break down the vital organs as a source of protein.

Around the world the rates of wasting have been dropping. However, according to the World Health Organization and UNICEF, in 2014 there were 50 million children under the age of five that experienced these forms of wasting, and 16 million were severely wasted (UNICEF, 2015). Worldwide, these figures indicate that nearly 1 child in every 13 suffers from some form of wasting. The majority of these children live in Asia (34.3 million) and Africa (13.9 million).

Wasting can occur as a result of severe food shortages, regional diets that lack certain proteins and vitamins, or infectious diseases that inhibit appetite (Latham, 1997).

The consequences of wasting depend on how late in the progression of the disease parents and guardians seek medical treatment for their children. Unfortunately, in some cultures families do not seek treatment early, and as a result by the time a child is hospitalized the child often dies within the first three days after admission (Latham, 1997). Several studies have reported long- term cognitive effects of early malnutrition (Galler & Ramsey, 1989; Galler, Ramsey, Salt & Archer, 1987; Richardson, 1980), even when home environments were controlled (Galler, Ramsey, Morley, Archer & Salt, 1990). Lower IQ scores (Galler et al., 1987), poor attention (Galler & Ramsey, 1989), and behavioral issues in the classroom (Galler et al., 1990) have been reported in children with a history of serious malnutrition in the first few years of life.[6]

Milk Anemia

Milk Anemia in the United States: About 9 million children in the United States are malnourished (Children’s Welfare, 1998). More still suffer from milk anemia, a condition in which milk consumption leads to a lack of iron in the diet. This can be due to the practice of giving toddlers milk as a pacifier-when resting, when riding, when waking, and so on. Appetite declines somewhat during toddlerhood and a small amount of milk (especially with added chocolate syrup) can easily satisfy a child’s appetite for many hours. The calcium in milk interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well. Many preschools and daycare centers give toddlers a drink after they have finished their meal in order to prevent spoiling their appetites.[7]

Failure to Thrive

Failure to thrive (FTT) occurs in children whose nutritional intake is insufficient for supporting normal growth and weight gain. FTT typically presents before two years of age, when growth rates are highest. Parents may express concern about picky eating habits, poor weight gain, or smaller size compared relative to peers of similar age. Physicians often identify FTT during routine office visits, when a child’s growth parameters are not tracking appropriately on growth curves.

FTT can be caused by physical or mental issues within the child (such as errors of metabolism, acid reflux, anemia, diarrhea, Cystic fibrosis, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, cleft palate, tongue tie, milk allergies, hyperthyroidism, congenital heart disease, etc.) It can also be caused by

caregiver’s actions (environmental), including inability to produce enough breastmilk, inadequate food supply, providing an insufficient number of feedings, and neglect. These causes may also co-exist. For instance, a child who is not getting sufficient nutrition may act content so that caregivers do not offer feedings of sufficient frequency or volume, and a child with severe acid reflux who appears to be in pain while eating may make a caregiver hesitant to offer sufficient feedings.[8]

In this video, Dr. Boise reviews benefits and challenges of breastfeeding, recommendations for introducing solid foods, and types of malnutrition children may experience.

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Infant Formula by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- When, What, and How to Introduce Solid Foods by the CDC is in the public domain ↵

- Infant Meals by the USDA is in the public domain ↵

- Child and Adult Meals by the USDA is in the public domain ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Failure to Thrive by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵