123 Moral Development-Kohlberg & Gilligan

Lawrence Kohlberg: Moral Development

Kohlberg (1963) built on the work of Piaget and was interested in finding out how our moral reasoning changes as we get older. He wanted to find out how people decide what is right and what is wrong (moral justice). Just as Piaget believed that children’s cognitive development follows specific patterns, Kohlberg argued that we learn our moral values through active thinking and reasoning, and that moral development follows a series of stages. Kohlberg’s six stages are generally organized into three levels of moral reasons. To study moral development, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to children, teenagers, and adults. One of Kohlberg’s best known moral dilemmas is the Heinz dilemma:[1]

A woman was on her deathbed. There was one drug that the doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to produce. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1,000 which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said: “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So Heinz got desperate and broke into the man’s laboratory to steal the drug for his wife. Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not?[2]

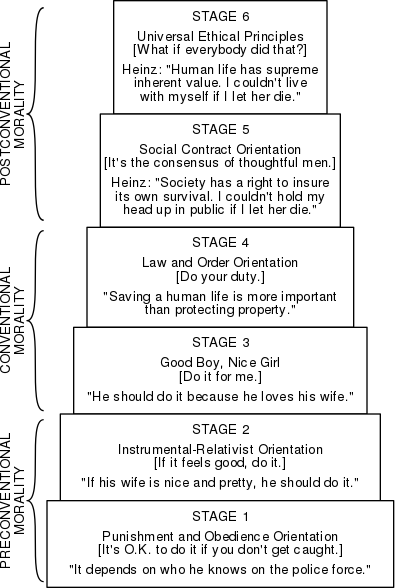

Based on their reasoning behind their responses (not whether they thought Heinz made the right choice or not), Kohlberg placed each person in one of the stages as described in the following image. Kohlberg’s stages are described in further detail below:[3]

Level One – Preconventional Morality

In stage one, moral reasoning is based on concepts of punishment. The child believes that if the consequence for an action is punishment, then the action was wrong. In the second stage, the child bases his or her thinking on self-interest and reward (“You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours”). The youngest subjects seemed to answer based on what would happen to the man as a result of the act. For example, they might say the man should not break into the pharmacy because the pharmacist might find him and beat him. Or they might say that the man should break in and steal the drug and his wife will give him a big kiss. Right or wrong, both decisions were based on what would physically happen to the man as a result of the act. This is a self- centered approach to moral decision-making. He called this most superficial understanding of right and wrong preconventional morality. Preconventional morality focuses on self-interest. Punishment is avoided and rewards are sought. Adults can also fall into these stages, particularly when they are under pressure.

|

Stage |

Description |

|

Stage 1 |

Focus is on self-interest and punishment is avoided. The man shouldn’t steal the drug, as he may get caught and go to jail. |

|

Stage 2 |

Rewards are sought. A person at this level will argue that the man should steal the drug because he does not want to lose his wife who takes care of him. |

Level Two – Conventional Morality

Those tested who based their answers on what other people would think of the man as a result of his act, were placed in Level Two. For instance, they might say he should break into the store, then everyone would think he was a good husband, or he should not because it is against the law. In either case, right and wrong is determined by what other people think. In stage three, the person wants to please others. At stage four, the person acknowledges the importance of social norms or laws and wants to be a good member of the group or society. A good decision is one that gains the approval of others or one that complies with the law. This he called conventional morality, people care about the effect of their actions on others. Some older children, adolescents, and adults use this reasoning.

|

Stage |

Description |

|

Stage 3 |

Focus is on how situational outcomes impact others and wanting to please and be accepted. The man should steal the drug because that is what good husbands do. |

|

Stage 4 |

People make decisions based on laws or formalized rules. The man should obey the law because stealing is a crime. |

Level Three- Post Conventional Morality

Right and wrong are based on social contracts established for the good of everyone and that can transcend the self and social convention. For example, the man should break into the store because, even if it is against the law, the wife needs the drug and her life is more important than the consequences the man might face for breaking the law. Alternatively, the man should not violate the principle of the right of property because this rule is essential for social order. In either case, the person’s judgment goes beyond what happens to the self. It is based on a concern for others; for society as a whole, or for an ethical standard rather than a legal standard. This level is called postconventional moral development because it goes beyond convention or what other people think to a higher, universal ethical principle of conduct that may or may not be reflected in the law. Notice that such thinking is the kind Supreme Court justices do all day when deliberating whether a law is moral or ethical, which requires being able to think abstractly. Often this is not accomplished until a person reaches adolescence or adulthood. In the fifth stage, laws are recognized as social contracts. The reasons for the laws, like justice, equality, and dignity, are used to evaluate decisions and interpret laws. In the sixth stage, individually determined universal ethical principles are weighed to make moral decisions. Kohlberg said that few people ever reach this stage.[6]

|

Stage |

Description |

|

Stage 5 |

Individuals employ abstract reasoning to justify behaviors. The man should steal the drug because laws can be unjust and you have to consider the whole situation. |

|

Stage 6 |

Moral behavior is based on self-chosen ethical principles. The man should steal the drug because life is more important than property. |

Video reviews the stages of Kohlberg’s theory of moral development. It also presents the Heinz dilemma with some additional questions for thought.

Evaluations of Kohlberg’s Theory

Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment and social rules and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. For one, children may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems, but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that this stage model is particularly appropriate for Western countries, rather than non-Western, samples in which allegiance to social norms (such as respect for authority) may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). In addition, there is little correlation between how children score on the moral stages and how they behave in real life.

Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it may describe the moral development of boys better than it describes that of girls. Carol Gilligan has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. Although there is little evidence that boys and girls score differently on Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), it is true that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000).[8]

Carol Gilligan: Morality of Care

Carol Gilligan, whose ideas center on a morality of care, or system of beliefs about human responsibilities, care, and consideration for others, proposed three moral positions that represent different extents or breadth of ethical care. Unlike Kohlberg, or Piaget, she does not claim that the positions form a strictly developmental sequence, but only that they can be ranked hierarchically according to their depth or subtlety. In this respect her theory is “semi- developmental” in a way similar to Maslow’s theory of motivation (Brown & Gilligan, 1992; Taylor, Gilligan, & Sullivan, 1995). The following table summarizes the three moral positions from Gilligan’s theory:

|

Moral Positions |

Definition of What is Morally Good |

|

Position 1: Survival Orientation |

Action that considers one’s personal needs only |

|

Position 2: Conventional Care |

Action that considers others’ needs or preferences but not one’s own |

|

Position 3: Integrated Care |

Action that attempts to coordinate one’s own personal needs with those of others |

Position 1: Caring as Survival

The most basic kind of caring is a survival orientation, in which a person is concerned primarily with his or her own welfare. As a moral position, a survival orientation is obviously not satisfactory for classrooms on a widespread scale. If every student only looked out for himself or herself alone, classroom life might become rather unpleasant. Nonetheless, there are situations in which caring primarily about yourself is both a sign of good mental health and also relevant to teachers. For a child who has been bullied at school or sexually abused at home, for example, it is both healthy and morally desirable to speak out about the bullying or abuse— essentially looking out for the victim’s own needs at the expense of others’, including the bully’s or abuser’s. Speaking out requires a survival orientation and is healthy because in this case, the child is at least caring about herself.

Position 2: Conventional Caring

A more subtle moral position is caring for others, in which a person is concerned about others’ happiness and welfare, and about reconciling or integrating others’ needs where they conflict with each other. In classrooms, students who operate from Position 2 can be very desirable in some ways; they can be kind, considerate, and good at fitting in and at working cooperatively with others. Because these qualities are very welcome in a busy classroom, it can be tempting for teachers to reward students for developing and using them for much of their school careers. The problem with rewarding Position 2 ethics, however, is that doing so neglects the student’s identity—his or her own academic and personal goals or values. Sooner or later, personal goals, values and identity need attention, and educators have a responsibility for assisting students to discover and clarify them. Unfortunately for teachers, students who know what they want may sometimes be more assertive and less automatically compliant than those who do not.

Position 3: Integrated Caring

The most developed form of moral caring in Gilligan’s model is integrated caring, the coordination of personal needs and values with those of others. Now the morally good choice takes account of everyone including yourself, not everyone except yourself.

In classrooms, integrated caring is most likely to surface whenever teachers give students wide, sustained freedom to make choices. If students have little flexibility about their actions, there is little room for considering anyone’s needs or values, whether their own or others’. If the teacher says simply, “Do the homework on page 50 and turn it in tomorrow morning,” then compliance becomes the main issue, not moral choice. But suppose instead that she says something like this: “Over the next two months, figure out an inquiry project about the use of water resources in our town. Organize it any way you want—talk to people, read widely about it, and share it with the class in a way that all of us, including yourself, will find meaningful.”

Although an assignment this general or abstract may not suit some teachers or students, it does pose moral challenges for those who do use it. Why? For one thing, students cannot simply carry out specific instructions, but must decide what aspect of the topic really matters to them. The choice is partly a matter of personal values. For another thing, students have to consider how the topic might be meaningful or important to others in the class. Third, because the time line for completion is relatively far in the future, students may have to weigh personal priorities (like spending time with family on the weekend) against educational priorities (working on the assignment a bit more on the weekend). Some students might have trouble making good choices when given this sort of freedom—and their teachers might therefore be cautious about giving such an assignment. But in a way these hesitations are part of Gilligan’s point: integrated caring is indeed more demanding than the caring based on survival or orientation to others, and not all students may be ready for it.[9]

Video describes how Gilligan’s theory contrasts with Kohlberg’s theory and how gender plays a role in the development of Gilligan’s theory. The three stages of Gilligan’s theory are also explained and illustrated with an example. Please note: The video refers to these three stages as preconventional, conventional, and post conventional, while your textbook refers to the three stags as survival orientation, conventional care, and integrated care.

- Lifespan Development – Module 6: Middle Childhood references Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology by Laura Overstreet, which is licensed under CC BY ;Beginning Psychology – Chapter 6: Growing and Developing by Charles Stangor is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Heinz Dilemma by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Beginning Psychology – Chapter 6: Growing and Developing by Charles Stangor is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Educational Psychology - 4.5 Moral Development: forming a sense of rights and responsibilities by CNX Psychology is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Contemporary Educational Psychology/Chapter 3: Student Development/Moral Development by Wikibooks is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (sections modified by Courtney Boise) ↵