115 Sex during Adolescence

The Brain and Sex

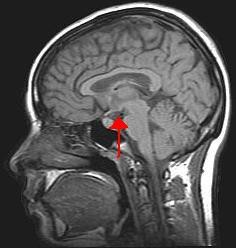

The brain is the structure that translates the nerve impulses from the skin into pleasurable sensations. It controls nerves and muscles used during sexual behavior. The brain regulates the release of hormones, which are believed to be the physiological origin of sexual desire. The cerebral cortex, which is the outer layer of the brain that allows for thinking and reasoning, is believed to be the origin of sexual thoughts and fantasies. Beneath the cortex is the limbic system, which consists of the amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and septal area. These structures are where emotions and feelings are believed to originate, and are important for sexual behavior.

The hypothalamus is the most important part of the brain for sexual functioning. This is the small area at the base of the brain consisting of several groups of nerve-cell bodies that receives input from the limbic system. Studies with lab animals have shown that destruction of certain areas of the hypothalamus causes complete elimination of sexual behavior. One of the reasons for the importance of the hypothalamus is that it controls the pituitary gland, which secretes hormones that control the other glands of the body.

Hormones

Several important sexual hormones are secreted by the pituitary gland. Oxytocin, also known as the hormone of love, is released during sexual intercourse when an orgasm is achieved.

Oxytocin is also released in biological females when they give birth or are breast-feeding; it is believed that oxytocin is involved with maintaining close relationships. Both prolactin and oxytocin stimulate milk production in females. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is responsible for ovulation in females by triggering egg maturity; it also stimulates sperm production in biological males. Luteinizing hormone (LH) triggers the release of a mature egg in females during the process of ovulation.

In males, testosterone appears to be a major contributing factor to sexual motivation. Vasopressin is involved in the male arousal phase, and the increase of vasopressin during erectile response may be directly associated with increased motivation to engage in sexual behavior.

The relationship between hormones and female sexual motivation is not as well understood, largely due to the overemphasis on male sexuality in Western research. Estrogen and progesterone typically regulate motivation to engage in sexual behavior for biological females, with estrogen increasing motivation and progesterone decreasing it. The levels of these hormones rise and fall throughout an individual’s menstrual cycle. Research suggests that testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin are also implicated in female sexual motivation in similar ways as they are in males, but more research is needed to understand these relationships.

By the end of high school, more than half of adolescents report having experienced sexual intercourse at least once, though it is hard to be certain of the proportion because of the sensitivity and privacy of the information. (Center for Disease Control, 2004; Rosenbaum, 2006).[1]

While sexual activity during adolescence can be a normative part of development during this period, adolescence are at increased likelihood for engaging in risky sexual behaviors such as sex without the use of contraceptives. Adolescents who engage in risky sexual behavior have a greater chance of pregnancy or a sexually transmitted infection (STI; Orihuela et al., 2020).[2]

Teen Pregnancy

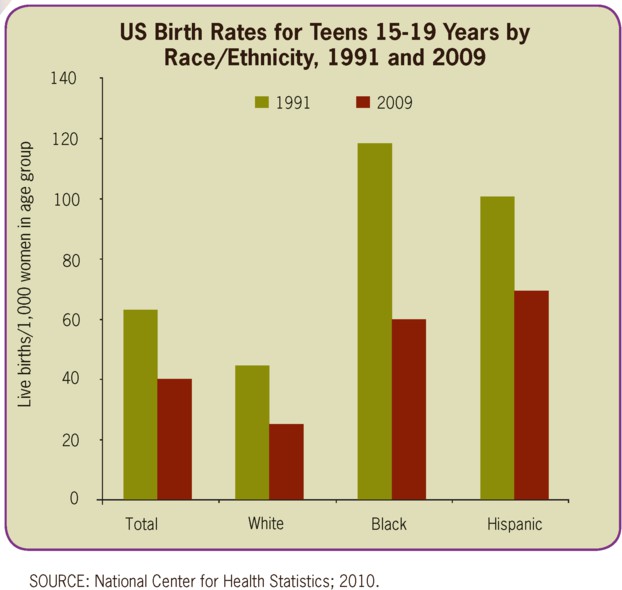

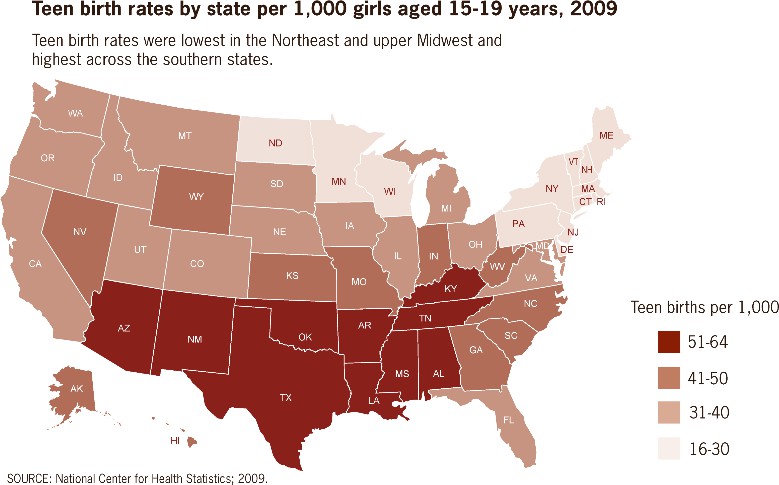

Although adolescent pregnancy rates have declined since 1991, teenage birth rates in the United States are higher than most industrialized countries. In 2014, females aged 15–19 years experienced a birth rate of 24.2 per 1,000 women. This is a drop of 9% from 2013. Birth rates fell 11% for those aged 15–17 years and 7% for 18–19 year-olds. It appears that adolescents seem to be less sexually active than in previous years, and those who are sexually active seem to be using birth control (CDC, 2016).

|

|

Risk Factors for Adolescent Pregnancy

Miller, Benson, and Galbraith (2001) found that parent/child closeness, parental supervision, and parents’ values against teen intercourse (or unprotected intercourse) decreased the risk of adolescent pregnancy. In contrast, residing in disorganized/dangerous neighborhoods, living in a lower SES family, living with a single parent, having older sexually active siblings or pregnant/parenting teenage sisters, early puberty, and being a victim of sexual abuse place adolescents at an increased risk of adolescent pregnancy.

Consequences of Adolescent Pregnancy

After a child is born life can be difficult for a teenage mother. Only 40% of teenagers who have children before age 18 graduate from high school. Without a high school degree, her job prospects are limited and economic independence is difficult. Teen mothers are more likely to live in poverty and more than 75% of all unmarried teen mothers receive public assistance within 5 years of the birth of their first child. Approximately, 64% of children born to an unmarried teenage high-school dropout live in poverty. Further, a child born to a teenage mother is 50% more likely to repeat a grade in school and is more likely to perform poorly on standardized tests and drop out before finishing high school (March of Dimes, 2012).[3]

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or venereal diseases (VDs), are illnesses that have a significant probability of transmission by means of sexual behavior, including vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral sex. It’s important to mention that some STIs can also be contracted by sharing intravenous drug needles with an infected person, through childbirth, or breastfeeding. Common STIs include:

- chlamydia;

- herpes (HSV-1 and HSV-2);

- human papillomavirus (HPV);

- gonorrhea;

- syphilis;

- trichomoniasis;

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014), there was an increase in the three most common types of STDs in 2014. Those most affected by STDS include younger, gay/bisexual males, and females. The most effective way to prevent transmission of STIs is to practice abstinence, (not participating in sexual intercourse), safe sex, and to avoid direct contact of skin or fluids which can lead to transfer with an infected partner. Proper use of safe-sex supplies (such as male condoms, female condoms, gloves, or dental dams) reduces contact and risk and can be effective in limiting exposure; however, some disease transmission may occur even with these barriers.[4]

Practicing safe sex is important to one’s physical health. In the following section we’ll look at elements of adolescent health, including sleep, diet, and exercise.

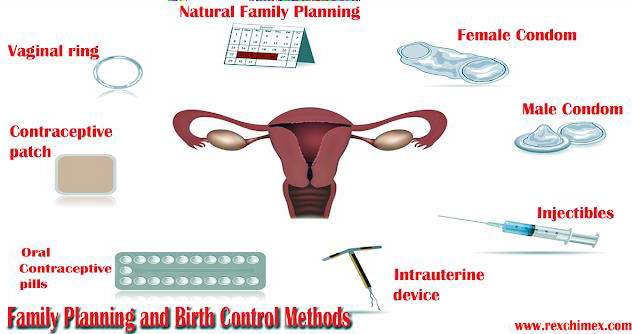

Contraceptive Methods and Protection from Sexually Transmitted Infection

There are many methods of contraception that sexually active adolescents can use to reduce the chances of pregnancy.[5]

|

Method |

Description |

Failure Rate |

|

Intrauterine Contraception (IUD) |

An IUD is a small device that is shaped in the form of a “T” placed inside the uterus |

0.1-0.8% |

|

Implant |

A single, thin rod that is inserted under the skin of a biological female’s upper arm. |

0.01% |

|

Injection |

Injections or shots of hormones to prevent pregnancy are given in the buttocks or arm every three months. |

4% |

|

Oral contraceptives |

Also called “the pill,” contain the hormones to prevent pregnancy. A pill is taken at the same time each day. |

7% |

|

Patch |

This skin patch is worn on the lower abdomen, buttocks, or upper body and releases hormones to prevent pregnancy into the bloodstream. A new patch once a week for three weeks and then left off for a week. |

7% |

|

Hormonal vaginal contraceptive ring |

The ring is placed in the vagina and releases the hormones to prevent pregnancy. It is worn for three weeks. A week after it is removed a new ring is placed. |

7% |

|

Spermicide |

These kill sperm and come in several forms—foam, gel, cream, film, suppository, or tablet. They are placed in the vagina before intercourse. |

21% |

|

Diaphragm or cervical cap |

A cup that is placed inside the vagina to cover the cervix to block sperm. It is inserted with spermicide before sexual intercourse. |

17% |

|

Sponge |

This contains spermicide and is placed in the vagina where it fits over the cervix. |

14-27% |

|

Male condom |

Worn (single use) by the biological male over the penis to keep sperm from getting into a biological female’s body. |

13% |

|

Female condom |

Worn (single use) by the biological female inside the vagina to keep sperm from getting into a biological female’s body. |

21% |

|

Natural Family Planning |

During a regular menstrual cycle, fertile days can be predicted. Sexual intercourse can be avoided on those days. |

2-23% |

|

Copper IUD |

Can be inserted up to 5 days after sexual intercourse |

<1%[7] |

|

Emergency contraceptive pills |

Can be taken up to 5 days after sexual intercourse and may be available over-the-counter. |

1-10%[8] |

In choosing a birth control method, dual protection from the simultaneous risk for HIV and other STIs also should be considered. Although hormonal contraceptives and IUDs are highly effective at preventing pregnancy, they do not protect against STIs, including HIV. Consistent and correct use of the male latex condom reduces the risk for HIV infection and other STIs, including chlamydial infection, gonococcal infection, and trichomoniasis.[9]

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Written by Courtney Boise ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Contraception by the CDC is in the public domain ↵

- How effective is emergency contraception? (2016). Retrieved from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/contraception/how-effective-emergency-contraception/ ↵

- David G. Weismiller M.D., Sc.M (2004). Emergency Contraception. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/0815/p707.html (modifications to all sections made by Courtney Boise) ↵

- Child Growth and Development by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵