14

Evan Layne Johnson, Ph.D., Florida SouthWestern State College

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

|

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

|

Introduction

Walking the halls at school, we tend to group people by their clothing style. He wears a letterman’s jacket, jeans, and sneakers; he’s a jock. She wears designer boots, skirt, blouse, and purse; she’s a wealthy princess. He wears work boots, ripped jeans, flannel, and has long hair; he’s grunge. She wears a frumpy skirt, black hoodie, dirty Chuck Taylors, and bangs in her eyes; she’s a weirdo. He wears a sweater, high-water pants, and a digital watch; he’s a nerd.

Figure 1: “The Breakfast Club” movie poster.1

While I’ve just described the poster for the classic, 1985 movie “The Breakfast Club,” generalizing based on style is not just a Hollywood thing, nor does style only apply to clothing. We categorize music and listeners by style: Do they like rock, country, rap, or classical music? Do they like action, anime, comedy, horror, or superhero movies? What’s their style? (Or we might say, “What’s their vibe?”) Despite the saying, “There’s no accounting for taste,” we often—rightly, or wrongly—judge people and things based on style. Style determines the color and model of cars we buy, the restaurants we frequent, and our electronics. (As one student said, “Apple products are pretty.” True.) Style also determines what we avoid and reject.

Public speakers must also account for style in their speeches. Audiences notice a speaker’s style of language. A toast speech delivered at a wedding reception, for example, will have a different style depending on whether it is delivered in a church or in a bar. If we are crass in the wrong setting, or too pious in the wrong setting, our language will clash with our audience’s expectations. Thus, we must be able to adapt our style to various situations.

Style is one of the five “canons,” or categories, in classical public speaking theory.2 The other four canons—invention, arrangement, memory, and delivery—are dealt with in other chapters of this book, but this chapter covers a speaker’s use of stylized language. To do so, this chapter first defines appropriate style, then discusses the stylistic goals of having clarity and correctness in our speech. Lastly, this chapter details how to make our speeches more vivid and memorable by using figurative, rhythmic, parallel, and ironic language.

Appropriateness: Plain, Moderate, and Grand Style

Style for the ancient Greeks fell on a continuum between plain and grand. While we can be plainspoken and use slang in much of our daily interaction with friends, it is not appropriate to say “ain’t” and “gonna” and “tryna” in job interviews and presentations for class or work. Thus, we adjust our style to be more- or less-formal based on the situation. For example, people working in retail or customer service adjust their style based on the customer. If a server approaches a well-dressed, retired person in a sit-down restaurant, they may say, “Good evening, sir/ma’am. Would you care to hear the specials this evening?” However, at a fast-food restaurant, a young cashier may welcome someone their age by saying, “S’up? What can I getcha?” The former is spoken in a grander style, and the latter is a plainer style. Context affects style.

The style path has a ditch on each side, then. If the speaker’s style is too plain for the scenario, they will be labeled as folksy or disrespectful, or worse. It is one thing for country singer Luke Bryan to drop the Gs in his song “Huntin’, Fishin’, Lovin’ Every Day,” but when the Former Governor of Alaska, Sarah Palin, was running for Vice President with Senator John McCain in 2008, that same tactic got her a reputation for being too folksy and plainspoken. (Gov. Palin is far from the only person to employ this common rhetorical strategy.) What goes over in a rural context, may not fit an urban context. The language used locally, may not fly nationally.

On the contrary, one can be too grand, or ornamented, in their speech, and hit the ditch on the other side of the style path. Few of us will ever meet royalty, the president, or the Pope, so there is little need to access the far reaches of highly-ornamented style, such as Shakespearian English or the terminology of the King James Bible (i.e. thee, thou, thy, spake, begat, etc.). If you start using archaic language in your speeches, audiences will quickly take note, and some people will tune out. If you use overly technical and sophisticated sounding language, an audience may feel as though you are talking down to them or patronizing them. An offended audience is hard to win back.

While we adjust our style to be grander or plainer based on context, then, we are often aiming for a moderate style. In classroom speeches, job interviews, and workplace presentations, we will mostly use moderate to moderately-grand stylized language. So how do we do that?

Clarity

To help achieve a moderate style, this chapter focuses on three broad concepts: clarity, correctness, and vividness—each with sub-topics.3 First, considering clarity, it is the quality of speaking with clear, concise language. Clear language avoids wordiness. Instead of saying, “At the end of the day, the family, as a whole, couldn’t pay their rent,” just say, “The family couldn’t pay their rent on time.” The word “family” is already plural, so adding “as a whole” is redundant. Moreover, “At the end of the day” is a filler phrase, or padding, which should be cut to reduce wordiness.

Another way to clarify your writing style is to avoid jargon and acronyms. Every workplace, religion, sport, or hobby uses jargon—or a technical vocabulary—among their peers, but if we want to be understood by a general audience, we need to strip jargon out of our speeches and put things in everyday, common terms. The military is famous for jargon (e.g. “I’m gonna hit the head” means I’m going to use the bathroom). It’s also renowned for acronyms: AWOL, IED, MRE, etc. If giving a speech to other enlisted soldiers or veterans, a speaker can include such insider language. However, such jargon and acronyms are inappropriate for a civilian audience and should be avoided to achieve clarity and not make the audience feel like outsiders.

Clarity is also enhanced by using concrete terms, rather than abstract terms. A memorable example of abstraction comes from legendary comedian George Carlin. He claims the Army kept renaming the same phenomena:

- “shell shock” (WWI)

- “battle fatigue” (WWII)

- “operational exhaustion” (Korean War)

- “post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” (Vietnam War until today)

Carlin claims that repeatedly renaming the condition made a concrete problem increasingly abstract and stripped the humanity and agency from the term. “Shell shock” was a two-syllable, simple term that Carlin says, “almost sounded like the guns themselves.” Abstracting the terms to a complicated eight-syllables of clinical jargon, Carlin notes, likely kept commanders and families from taking the condition seriously, which subsequently kept suffering soldiers and veterans from getting treatment.

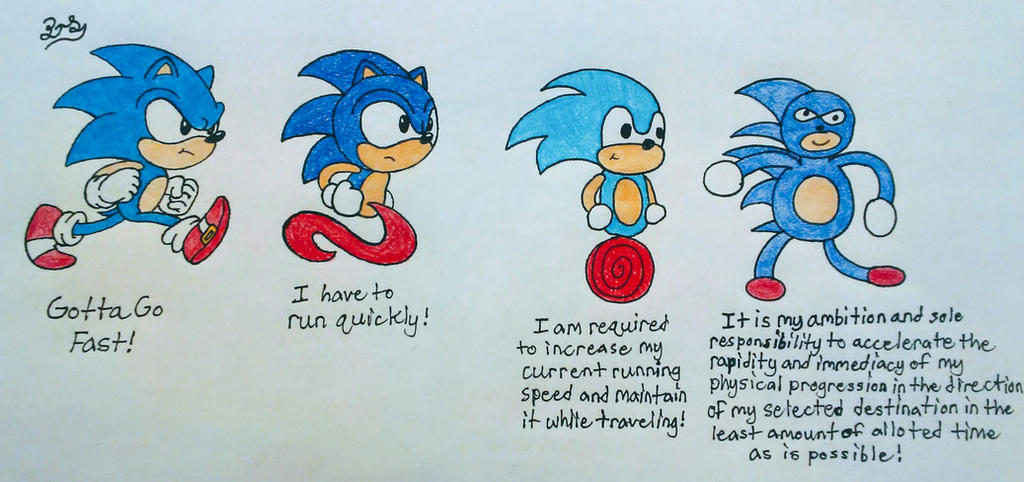

For a less serious example of abstract terms, see the Sonic the Hedgehog meme. As his catchphrase gets wordier, the image gets blurrier. The same thing happens when you are too wordy in your speeches and essays—your ideas get fuzzy.

Figure 2: Increasingly Verbose Sonic Meme4

Figure 2: Increasingly Verbose Sonic Meme4

Finally, regarding clarity, the speaker can be clearer by favoring active voice rather than passive voice. In certain social situations, one may use passive voice to displace agency and save face. Your child may tell you, “All the candy was eaten” or, “The glass got broken.” Of course, the parent’s next question will be “Who ate it?” or “Who broke it?” because passive voice hides behind vagary. Alternately, using active voice re-instates specificity, agency, and ownership. “I ate the cookies.” “I broke the glass, and I’m sorry.” Now that the transgression has been “owned,” it can be forgiven, and we can move on, but it was a passive voice mystery that needed to be solved when the thing ambiguously “was eaten” or “got broken.” So, take ownership in your writing. If you can say “by zombies” after the verb, it may be in passive voice, and the sentence should likely be revised to active voice . . . by zombies.

Correctness

A former student once wrote in her informative speech outline that Amelia Earhart’s pioneering flights “impacted the world.” This phrasing is unfortunate. While it is true that Earhart was a trailblazer—first female pilot to complete a solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean—she also died in a plane crash: a literal “impact.” So, if you are using “impact” metaphorically, don’t. Use “affect” instead. (Also, “impactful” should be “affective.”) While a meteorite impacts the earth, watching a meteor shower has an emotional affect on you, not an impact—unless you get knocked out, and awake next to a rock. Then you were “impacted.”

Correctness includes precise grammar and word choices. Did the source “collaborate” or “corroborate”? Did we “adapt” or “adopt”?

- elegant or eloquent

- expand or expound

- farther or further

- regardless or irregardless

- sit or set

- venerable or vulnerable

Grammatical issues and word choices arise regularly. When in doubt, look it up, and get it right.

Sometimes a word may even be technically correct according to its denotation, or dictionary definition. However, language is alive, and words accrue cultural meaning, or connotation. A “thug” may just be a troubled person in a “gang,” or a group, but those words have acquired politically and racially-charged connotations. The word “moist” is disliked by many, presumably because of connotation, not denotation. Depending on who is saying what to whom, many words become positive or negative:

- frugal

- evangelical

- law and order

- liberal

- patriot

For this speaker or that audience, these words may have wildly divergent meanings. Hence, we need to become vocabulary savvy to navigate many terms’ cultural and political connotations.

CASE STUDY: In 1987, near the end of the Cold War, President Ronald Reagan gave a speech at the Berlin Wall. The wall literally separated East and West Germany, but it was also symbolically the “iron curtain” separating democratic and communist countries after WWII. As the Soviet Bloc destabilized in the late 80s, this wall was metaphorically crumbling, and Reagan’s speech needed an explosive phrase to prompt a shift from the metaphorical to a literal crumbling of the wall he stood beside.5 Hence, the climactic line of Reagan’s speech became, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”6 However, that memorable line evolved from:

- “take down this wall,” to

- “get rid of this wall,” to

- “dismantle this wall,” to

- “tear down this wall.”

The speech’s first draft—“take down this wall”—is not an applause line. “Take” is a weak verb. You can take a nap, a drink, a walk, or whatever. It is a versatile, yet vague, verb. A German activist suggested getting “rid of this wall,” which is better, but still has the wrong connotation. You rid something small and pestering, such as sugar from a diet, acne from a face, bats from the attic. You don’t “rid” yourself of something huge, imposing, and immoveable. Another option was to “dismantle” the wall, which Reagan wrote in a memo the year prior. However, the connotation is still wrong. “Dismantle” is too clinical, too calm—as if the wall was made of bricks, and the dismantlers were trying to save every brick to re-build the wall across town. Finally, someone wrote “tear” it down, which has the right denotation and connotation. Like the protestors who would soon do so, the audience can envision tearing a wall down with sledgehammers and brute strength: climbing it, toppling it, and eventually bulldozing it. They tore it down.

Figure 3: Smashing Berlin Wall with sledgehammer.7 Figure 4: Toppling a section of the Berlin Wall.8

Inexperienced writers often think the way to improve their writing is to add adjectives. That writer may have revised the original draft to say something like, “Mr. Gorbachev, take down this brutish, concrete, divisive wall!” But adding adjectives is not the way. Instead, a more experienced use of stylized language is to strengthen abstract verbs in the writing. “Take” becomes “tear,” and the precision, style, and speech improve. No adjectives needed.

Vividness: Figurative, Rhythmic, Parallel & Ironic Language

While we want to be concise and precise with our language, we also want to make it vivid, which includes adding some figures of speech for rhetorical effect. Either to persuade your audience, identify with them, or make them emote, you want to incorporate memorable language. The rest of the chapter discusses figures of speech that are especially useful in speeches, as compared to essays. Since you have a live, listening audience, we need to remember to “speak for the ear, and not for the eye.” In other words, use some vivid language, such as figurative, rhythmic, parallel, and occasional ironic language.

The starting point for figurative language is metaphor. Metaphors describe one thing in terms of another thing. Take the phrase, “Love is a rose.” Here, to describe one thing (love), the imagery, or figure, of another thing is invoked (a rose). If the speaker uses “like” or “as” in the comparison, it would be a simile (i.e. Robert Burns’ poem says, “O my love is like a red, red rose”). Unlike poetry, though, a live speech audience only gets to listen once, and cannot necessarily re-read or re-watch the speech. Hence, the speaker may have to expound upon the idea. It is a useful exercise, then, to expand one metaphor or simile per speech into an analogy by adding two-to-three more details. Why is love like a rose? What are the characteristics of roses? A rose has delicate petals and a nice fragrance, but it has thorns for self-protection. The flower is alive, but if picked it will wilt. It needs nurturing: food and water, good soil, and attention. If we add a few of these details to our metaphor about love being a rose, we can stretch it into an analogy, as Poison began to do in their 1988 hit song “Every rose has its thorns.”

CLASS ACTIVITY: Many catchy sayings are great at first but get over-used and become clichés over time. In your writing, avoid clichés! As a class activity, try to complete this line: “Love is a/an_____________.” First, get all the love clichés out of your system:

- love is a rose

- love is a battlefield

- love is like a rollercoaster

- love is a drug

- love is blind, etc.

Once the clichés have been exhausted, each student should try to write three original things about love. Then expand one of the original metaphors or similes into an analogy by giving the reasoning behind it. If the class is around lunch time, students may write things like, “Love is like a pizza fresh from the oven.” Push beyond that and try to say something original and deep. Make it a deep dish, if you will.

Aiming for originality should lead to creativity and some pleasant surprises. This is known as the Principle of Deviation: deviate from the norm, say the unexpected, say something original. When you say expected clichés, people tune out, and the audience may not even understand. When I ask a class of twenty-five students what the cliché, “Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth” means, only two or three know it means “be grateful for a gift.” And if I ask them why it means that, typically only one person knows. This agrarian phrase is no longer understandable for 90% of the audience. Few have horses, and even fewer know that one looks into a horse’s mouth to get an indication of age (length of teeth) and health (color of gums). A phrase that has lost its meaning should not be used in a speech. If you want to use an analogy about being grateful, a modern equivalent may be, “Don’t take your grandparents’ twenty-year old Toyota Corolla with 200,000 miles for granted when you turn 16.” At least this phrase is original and understandable. So put the clichés and the horses back in the barn, and instead say something unexpected.

A final way to effectively use figurative language is through personification, or giving things human or animal traits. A famous example of personification comes from T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Even without knowing that Eliot was a life-long cat lover, or that he wrote the poems that became the musical “Cats,” many readers will recognize that in these lines he personifies the fog as a cat. Fog does not have a back, a tongue, or the ability to leap or sleep, but cats do. So rather than saying, “It was foggy that evening,” Eliot has vivified the fog through original, figurative language.

Rhythmic Language

The primary ways to have rhythm in your writing are through rhyme and repetition. Unlike poetry, rhyme is rarely used in public speaking, so this section focuses on repetition instead. In an HBO poetry slam called “Brave New Voices”, Mike says,

Obviously, hands, arms, feet, sox, and shoes do not think, but the personification of these non-thinking things gets the listener’s attention. Mike also gets the listener’s attention through the repetition of the phrases “thinking about” and “I’m thinking about you.” And there are names for these types of repetition.

This excerpt repeats the phrase, “I’m thinking about you” three times, which is a triad. A triad is a type of repetition that phrases, or lists, things in groups of three. There is a phenomenon known as the Rule of Three, which says that sets of three seem complete and are therefore more pleasing or persuasive for the audience. A stool with three legs can stand, an argument with three points is more convincing, and a list of three things is memorable. Red, white, and blue is a triad of colors. President Lincoln’s famous quotation that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth” is memorable because it is a triad. Even though it is difficult to know how “of the people” and “by the people” differ, he includes both to make a triad. It worked, for audiences have remembered, and politicians have quoted this line for over 160 years.

Another example comes from Winston Churchill, who actually said, “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” However, people misremember this quotation as “blood, sweat, and tears,” which, according to the Rule of Three, is an improvement for memorability. Once you start noticing triads, you see and hear them everywhere—in speeches, mottos, clichés, and in book, song and movie titles:

- “I came, I saw, I conquered.” (Roman Emperor Julius Caesar)

- “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” (Book and film title)

- “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” (The Declaration of Independence)

- “Faith, hope, and love.”

- “Live, Laugh, Love.”

- “Location, location, location.”

- “Stop, drop, and roll.”

And there are many, many more examples. Thus, in your speeches, you may want to have three main points, cite three sources, and whenever you can, use a triad or three. Or, use another form of repetition to make your information memorable.

The most famous speech in American public address is the “I Have a Dream” speech by Martin Luther King Jr. This speech uses ample repetition by using a rhetorical tactic known as anaphora. Anaphora is the repetition of the beginning phrase of successive sentences. For example, King starts eight straight sentences with the phrase “I have a dream.” Then he ends the speech with ten sentences beginning, “Let freedom ring.”

Other orators have also used anaphora,

- Jesus of Nazareth begins eight straight sentences in “The Sermon on the Mount” with the phrase, “Blessed are the . . .” (a.k.a. “The Beatitudes”).

- Dr. Seuss says of Green Eggs and Ham, “I do not like them” six times.

Of course, one does not want to over-rely on repetition. Spreading eight “Blessed are . . .” statements across eight sentences works well, but jamming six “I do not like thems . . .” into one run-on sentence is too much. If two iterations of something is too little repetition for many audience members to notice, shoot for repeating three-to-five times. At any rate, try not to sound Seussian.

The flip side of anaphora is the less-commonly used epiphora. Epiphora repeats the ending of successive phrases. A shorter example from American public address comes from former President Bill Clinton, who said, “There is nothing wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America.” While only twice repeating two words (“with America”) may seem like too little repetition, this phrase also benefits from the antithesis between “right” and “wrong.” Hence, the phrase is memorable and stylish.

Other prominent examples of epiphora include:

- “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.”

- The 1970s Dr. Pepper commercial: “I’m a Pepper, he’s a Pepper, she’s a Pepper, we’re a Pepper, wouldn’t you like to be a Pepper, too?”

A live audience only gets one pass at hearing your speech and will only remember about 50% of what they hear immediately afterward. By the next day, many audience members may only remember about 10-to-20% of what was said. Therefore, don’t be afraid of using some repetition to help reinforce your points and the audience’s memory.

Another useful form of repetition in speeches is polyptoton. Polyptoton is the use of multiple variations of the same word in one sentence. Many words can be derived from the same root; the word “love,” for example, can vary to become loves, loved, lover, loving, lovely, lovingly, loveless, beloved, and unlovable. Polyptoton can be used to show connection, contrast, lend emphasis through repetition, and can even be used in an argument. One could argue that a techno song isn’t truly “music” if only a computer made it, and no musicians or musical instruments were involved. Or one could argue something is not “art” if it is created by artificial intelligence (AI) or 3D printing, and no artist painted or sculpted it? These are arguments from definition, using polyptoton.

Other famous examples of polyptoton include:

- “I dreamed a dream of dreams gone by.” (“Les Misérables”)

- “Love is not love which alters when it alteration finds, or bends with the remover to remove . . .” (Shakespeare)

- “Judge not, lest you be judged.” (Biblical proverb)

- “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” (Lord Acton)

- “Not as a call to battle, though embattled we are.” (President John F. Kennedy)

In addition to varying the volume, tone, and pace of our speech delivery to avoid becoming monotonous, we can vary our language.

Finally, a common means of repetition and rhythm is using alliteration. Alliteration is using two or more words in a sentence that start with the same letter. Many company names are alliterative:

- Best Buy

- Coca Cola

- Dunkin Donuts

- Peter Pan peanut butter

And a famous line from the “I Have a Dream” speech emphasizes alliteration: “I have a dream that my four little children . . . will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” This repetition of the K-sound (mostly with hard “Cs”) hits the audience’s ear: children, color, skin, content, character. Not only the fine sentiment, but the deft alliteration in this line makes it one of the most memorable phrases in American public address.

Of course, too much alliteration can be a problem, and even becomes a tongue twister, such as in the nursery rhyme “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” That’s just too much. So is the phrase, “She sells seashells by the seashore.” Thus, use alliteration, but don’t overdo it. Follow the Goldilocks Principle of not too much, not too little, but just enough repetition. Repeating twice is too few, but more than five times may be too many. Again, aim for repeating things three-to-five times.

Parallel Language

In addition to figurative and rhythmic language, parallelism makes a speaker’s style vivid. Parallelism is writing and speaking in such a way that two phrases, clauses, paragraphs, or arguments are similar in structure and resemble one another. Two specific means of parallelism discussed in the following paragraphs are chiasmus and antithesis.

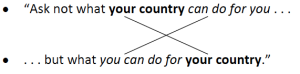

The term chiasmus comes from the Greek letter “X,” which is pronounced “kai” (rhymes with “tie”). This figure of speech involves inverting subject and predicate in successive phrases. If those phrases are diagrammed one atop the other, and lines are drawn between the similar portions, the diagram forms an “X,” which explains the name. Here is a diagram of President Kennedy’s most famous quote:

See the “X” in the diagram? “Your country” has gone from the start of the first phrase to the end of the second phrase, and vice versa with the words “can do for you,” which went back to front and were slightly re-ordered.

Other well-known chiasmi include:

- “Winners never quit, and quitters never win” (Vince Lombardi, NFL coach).

- Are you workinghard, or hardly working?

- When the going gets tough, the tough get going.

- “You can take the boy out of the country,

- but you can’t take the country out of the boy” (Carl Perkins, singer).

- God is good all the time, and all the time god is good.

- “Would you rather be a warrior in a garden,

- or a gardener in a war? (Miyamoto Musashi)

Hence, in a chiasmus, there is obvious parallelism between the first and second parts of a phrase achieved by swapping the same words around.

Another form of parallelism is antitheses. Antithesis features two opposite words in parallel phrases, such as the stock-market advice, “Buy low, sell high.” This exemplar has two parallel phrases, each with two words, and two sets of opposites. There is a thesis (“buy,” or acquire) and an anti-thesis (“sell,” or unload what you bought). There are also the antonyms: low and high. The English language is often reliant on antonyms: rich or poor, black or white, fat or thin, young or old, hot or cold, love or hate, near or far, good or evil. Since the world has many shades of gray, this terminology may cause people to engage polarized thinking and lose nuance. While polarization may become a problem in an interpersonal relationship or social situation, antithesis is useful in a public speech as a memorable, rhetorical device.

Famous antitheses include:

- “Down with dope, up with hope.” (Jesse Jackson)

- This antithesis also has alliteration and rhyme.

- “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard . . .” (President John F. Kennedy, 1962)

- “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” (Neil Armstrong, 1969)

- This antonym (small step vs. giant leap) also has a polyptoton (man/mankind).

Ironic Language

Recently, while driving in Cape Coral, I saw a car with a bumper sticker that read “0% Liberal.” This bumper sticker was on a Toyota Prius hybrid. At least to some degree, these words and actions contradict, and are ironic. This driver is—unwittingly—at least 1% liberal.

When someone says one thing but intends the opposite meaning by way of tone or inuendo, that is irony. While some in the audience may misunderstand traditional irony, or the use of sarcasm, there are ironic figures of speech that are more understandable and more common in public speaking. The speaker could point out coincidences, make a strange juxtaposition, or discuss surprising results in an ironic way. Two common ironic variations in public speaking are hyperbole and litotes.

Hyperbole is exaggeration for stylistic, rhetorical, or ironic effect. A hyperbolic speaker substitutes terms that overstate the case and over-shoot the mark so egregiously that the audience disbelieves the words and infers the speaker’s ironic intent. Examples include hyperbolic clichés, such as:

- My feet are killing me.

- I’m as thirsty as a camel.

- It’s the city that never sleeps.

- It cost an arm and a leg.

- I’m drowning in work.

Since we live in such a hyperbolic culture, saying “I died of embarrassment” likely won’t be memorable for the audience. Hence, if you are going to use hyperbole, go big, and be original.

Rather than getting more hyperbolic, though, an alternative would be to use the figure of speech litotes. Litotes is ironic understatement for rhetorical effect. Whereas hyperbole overstates and exaggerates, litotes understates, minimizes, or downplays. If you attend Mardi Gras and later describe it to your friends as “a low-key gathering,” it would be ironic understatement for comedic effect. Other examples of litotes include:

- “LeBron James is okay at basketball.”

- “There were a few people at the Taylor Swift concert.”

- “Elon Musk made a couple bucks last year.”

- Calling the Grand Canyon “a little ditch,” or the Rocky Mountains “some hills.”

- Saying, “You’re not wrong,” instead of “You’re right.”

- Saying, “That wasn’t half bad,” after a marvelous experience.

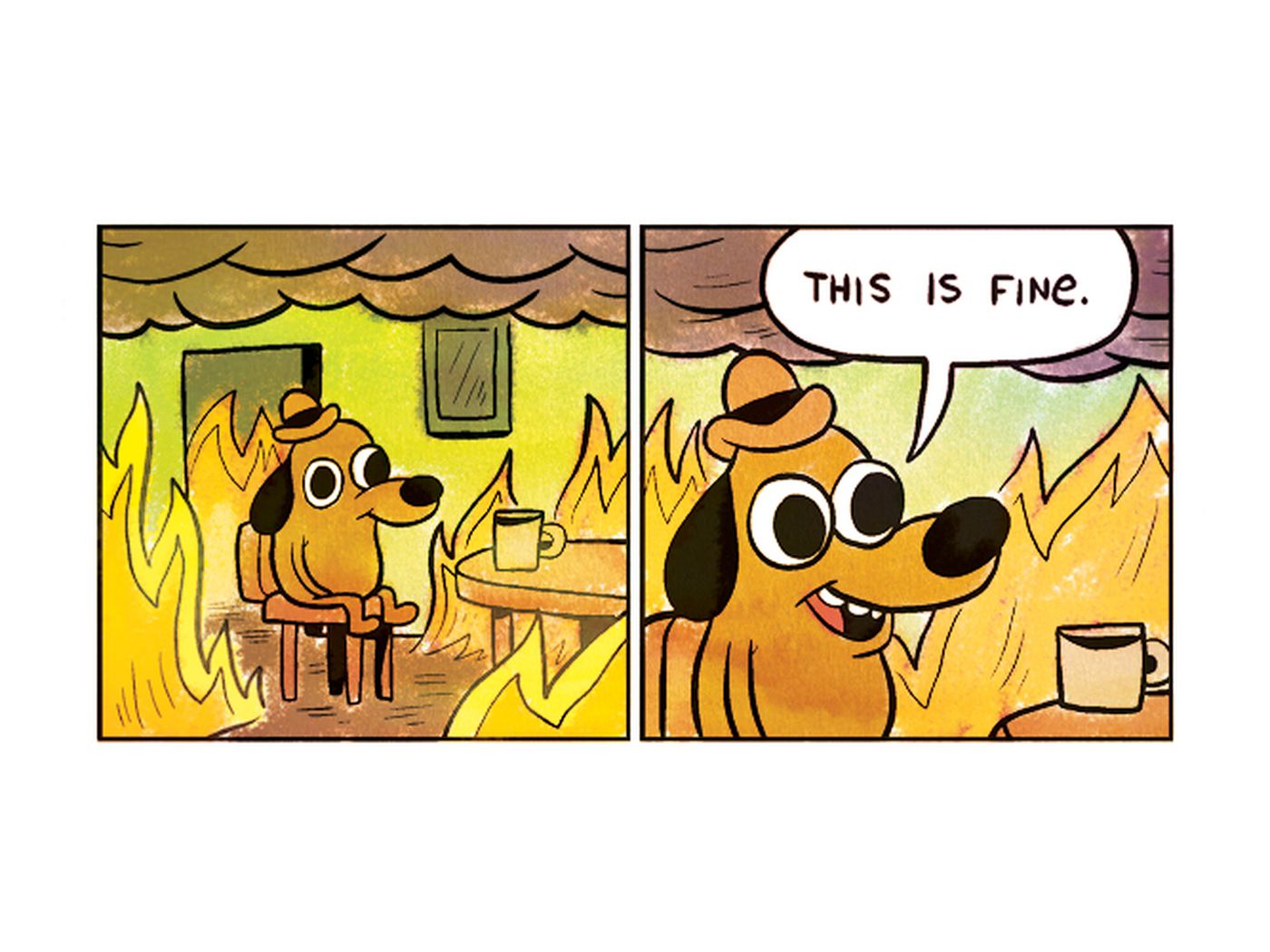

Additionally, the “This is fine” meme is litotes. Obviously, it is not “fine” to be sitting in a room bursting into flames and filling with smoke. Anyone in that situation should run and call for help. However, by sitting there, drinking coffee, and stating, “This is fine,” the cartoon achieves its rhetorical effect through ironic understatement to the point of comedic downplaying. In our hyperbolic culture, understatement like this is often more memorable than hyperbole.

Figure 5: “This is fine” meme, dog sitting in burning room.9

Conclusion

All language has style. Poetry may have a flowery style; scientific writing may have a sterile style, but it still has style. While we want to develop our own voice as writers and public speakers, we also want to mostly use a moderate style when job interviewing and making professional and classroom presentations. Both a plain style that uses slang and a grand style with overly-ornamented frills will lose a segment of our audience. Instead, talk in simple sentences with concrete terms, add original vivid imagery where appropriate, and adapt your language to your audience.

Five rules for writing from the novelist George Orwell summarize this chapter well:

- Avoid clichés.

- If a phrase or metaphor is familiar, cut it and write something original. Original phrases are memorable.

- Be direct and use concrete terms.

- Don’t use a long word if a short one will do.

- Be succinct.

- If you can cut a word, cut it. Avoid wordiness.

- Use active voice instead of passive voice.

- Give yourself agency; own it.

- Be understandable.

- If there is an everyday, English equivalent, use it. Try to avoid jargon, foreign phrases, and overly scientific language.

Why say “armoire” if you could say “wardrobe,” or even “closet”? Why say “somnambulism” when you could say “sleep walking”? Why call someone a “beverage dissemination officer” instead of a “bartender”? Keep it simple and be understood.

To this summary, we add the advice to speak in vivid, memorable terms by using some figurative, rhythmic, parallel, and ironic language. The worst thing for a speaker would be failing to get or keep the audience’s attention during the speech. The next worst thing would be failing to say anything memorable. Using style in your speeches is one way to avoid both of those problems. Neither pad your writing with flowery, opaque phrases, nor bore your audience with sterile and dry language. Use a moderate style, but have style, nonetheless.

As the architect Frank Lloyd Wright said, “Form follows function.” In other words, style may not be as important as content. However, that phrase is only memorable because it is a triad with fabulous alliteration. More irony: we would forget the dictum to subordinate style to content if the saying about content wasn’t stylish. So too, without a stylized speech, your audience may never hear or remember your content.

Reflection Questions

- What style of language is most appropriate for public speakers to use in classroom and work presentations

- Why are wordiness, jargon, abstraction, and clichés problems?

- What is the difference between denotation and connotation?

- What is the Principle of Deviation?

- What are four ways to add figurative language to a speech?

- What are five ways to make language more rhythmic?

- What are two means to develop parallelism in your language?

- What are two ways to use ironic language in a speech?

Key Terms

Active vs. Passive Voice

Alliteration

Anaphora

Antithesis

Appropriateness: Plain, Moderate, and Grand Style

Chiasmus

Clarity: Wordiness, Jargon, Acronyms, Clichés

Concrete vs. Abstract terms

Correctness

Denotation vs. Connotation

Epiphora

Figurative language

Goldilocks Principle

Irony: Hyperbole, Litotes

Metaphor, Simile, and Analogy

Parallelism

Personification

Polyptoton

Principle of Deviation

Repetition

Rhythmic language (rhythm)

Rule of Three

Triad

Vividness

References

Aristotle (1991). On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse (Trans. G. Kennedy). Oxford University Press.

Bizzell, P., & Herzberg, B. (2001). The rhetorical tradition: Readings from classical times to the present (2nd ed.). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Boethius (2001). An overview of the structure of rhetoric. In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Ed.s), The rhetorical tradition, (pp. 488-89). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Burke, K. (1969). A grammar of motives. University of California Press.

Carlin, G. (1990). Doin’it Again. MPI Media Group.

Churchill, W. (1940). Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat (First Speech as Prime Minister to the House of Commons). American Rhetoric. https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/winstonchurchillbloodtoiltearssweat.htm

Cicero (1954). Rhetorica ad Herennium. Translated by Harry Caplan. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press.

Eliot, T. S. (1963). The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, Collected Poems. www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/44212/the-love-song-of-j-alfred-prufrock

Fahnestock, J. (2011). Rhetorical Style: The Uses of Language in Persuasion. Oxford University Press.

Hariman, R. (1995). Political style: The artistry of power. University of Chicago Press.

Lincoln, A. (1863). Gettysburg address. American Rhetoric. https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/gettysburgaddress.htm

Mike. (2008). Thinking about you. HBO: Brave New Voices.

https://www.hbo.com/russell-simmons-presents-brave-new-voices

Orwell, G. (1946). Politics and the English Language. Horizon. https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/politics-and-the-english-language/

Osborn, M. (2018). Michael Osborn on metaphor and style. Michigan State University Press.

Reagan, R. (1987). Remarks at the Brandenburg Gate. American Rhetoric. https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/ronaldreaganbrandenburggate.htm