10

Amy Fara Edwards and Marcia Fulkerson, Oxnard College

Victoria Leonard, Lauren Rome, and Tammera Stokes Rice, College of the Canyons

Adapted by Jamie C. Votraw, Professor of Communication Studies, Florida SouthWestern State College

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

|

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

|

Figure 10.1: Abubaccar Tambadou1

Introduction

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) was founded on April 10, 1866. You may be familiar with their television commercials. They start with images of neglected and lonely-looking cats and dogs while the screen text says: “Every hour… an animal is beaten or abused. They suffer… alone and terrified…” Cue the sad song and the request for donations on the screen. This commercial causes audiences to run for the television remote because they can’t bear to see those images! Yet it is a very persuasive commercial and has proven to be very successful for this organization. According to the ASPCA website, they have raised $30 million since 2006, and their membership has grown to over 1.2 million people. The audience’s reaction to this commercial showcases how persuasion works! In this chapter, we will define persuasive speaking and examine the strategies used to create powerful persuasive speeches.

Figure 10.2: Caged Dogs 2

Defining Persuasive Speaking

Persuasion is the process of creating, reinforcing, or changing people’s beliefs or actions. It is not manipulation, however! The speaker’s intention should be clear to the audience in an ethical way and accomplished through the ethical use of methods of persuasion. When speaking to persuade, the speaker works as an advocate. In contrast to informative speaking, persuasive speakers argue in support of a position and work to convince the audience to support or do something.

As you learned in chapter five on audience analysis, you must continue to consider the psychological characteristics of the audience. You will discover in this chapter the attitudes, beliefs, and values of the audience become particularly relevant in the persuasive speechmaking process. A key element of persuasion is the speaker’s intent. You must intend to create, reinforce, and/or change people’s beliefs or actions in an ethical way.

Types of Persuasive Speeches

There are three types of persuasive speech propositions. A proposition, or speech claim, is a statement you want your audience to support. To gain the support of our audience, we use evidence and reasoning to support our claims. Persuasive speech propositions fall into one of three categories, including questions of fact, questions of value, and questions of policy. Determining the type of persuasive propositions your speech deals with will help you determine what forms of argument and reasoning are necessary to effectively advocate for your position.

Questions of Fact

A question of fact determines whether something is true or untrue, does or does not exist, or did or did not happen. Questions of fact are based on research, and you may find research that supports competing sides of an argument! You may even find that you change your mind about a subject when researching. Ultimately, you will take a stance and rely on credible evidence to support your position, ethically.

Today there are many hotly contested propositions of fact: humans have walked on the moon, the Earth is flat, Earth’s climate is changing due to human action, we have encountered sentient alien life forms, life exists on Mars, and so on.

Here is an example of a question of fact:

Recreational marijuana does not lead to hard drug use.

(or)

Recreational marijuana does lead to hard drug use.

Questions of Value

A question of value determines whether something is good or bad, moral or immoral, just or unjust, fair or unfair. You will have to take a definitive stance on which side you’re arguing. For this proposition, your opinion alone is not enough; you must have evidence and reasoning. An ethical speaker will acknowledge all sides of the argument, and to better argue their point, the speaker will convince the audience why their position is the “best” position.

Here is an example of a question of value:

Recreational marijuana use is immoral.

(or)

Recreational marijuana use is moral.

Questions of Policy

A question of policy advances a specific course of action based on facts and values. You are telling the audience what you believe should be done and/or you are asking your audience to act in a particular way to make a change. Whether it is stated or implied, all policy speeches focus on values. To be the most persuasive and get your audience to act, you must determine their beliefs, which will help you organize and argue your proposition.

Persuasive speeches on questions of policy must address three elements: need, plan, and practicality. First, the speaker must demonstrate there is a need for change (i.e., there is a problem). Next, the speaker offers the audience a plan (i.e., the policy solution) to address the problem. Lastly, the speaker shows the audience that the solution is practical. This requires that the speaker demonstrate how their proposed plan will address the identified problem without creating new problems.

Consider the topic of car accidents. A persuasive speech on a question of policy might focus on reducing the number of car accidents on a Florida highway. First, the speaker could use evidence from their research to demonstrate there is a need for change (e.g., statistics showing a higher-than-average rate of accidents). Then, the speaker would offer their plan to address the problem. Imagine their proposed plan was to permanently shut down all Florida highways. Would this plan solve the problem and reduce the number of accidents on Florida highways? Well, yes. But is it practical? No. Will it create new problems? Yes – side roads will be congested, people will miss work, kids will miss school, emergency response teams will be slowed, and tourism will decrease. The speaker could not offer such a plan and demonstrate that it is practical. Alternatively, maybe the speaker advocates for a speed reduction in a particularly problematic stretch of highway or convinces the audience to support increasing the number of highway patrol cars.

Here is an example of a question of policy:

Recreational marijuana use should be legal in all 50 states.

(or)

Recreational marijuana use should not be legal in all 50 states.

Persuasive Speech Organizational Patterns

There are several methods of organizing persuasive speeches. Remember, you must use an organizational pattern to outline your speech (think back to chapter eight). Some professors will specify a specific pattern to use for your assignment. Otherwise, the organizational pattern you select should be based on your speech content. What pattern is most logical based on your main points and the goal of your speech? This section will explain five common formats of persuasive outlines: Problem-Solution, Problem-Cause-Solution, Comparative Advantages, Monroe’s Motivated Sequence, and Claim to Proof.

Problem-Solution Pattern

Sometimes it is necessary to share a problem and a solution with an audience. In cases like these, the problem-solution organizational pattern is an appropriate way to arrange the main points of a speech. It’s important to reflect on what is of interest to you, but also what is critical to engage your audience. This pattern is used intentionally because, for most problems in society, the audience is unaware of their severity. Problems can exist at a local, state, national, or global level.

For example, the nation has recently become much more aware of the problem of human sex trafficking. Although the US has been aware of this global issue for some time, many communities are finally learning this problem is occurring in their own backyards. Colleges and universities have become engaged in the fight. Student clubs and organizations are getting involved and bringing awareness to this problem. Everyday citizens are using social media to warn friends and followers of sex-trafficking tricks to look out for.

Let’s look at how you might organize a problem-solution speech centered on this topic. In the body of this speech, there would be two main points; a problem and a solution. This pattern is used for speeches on questions of policy.

Topic: Human Sex Trafficking

General Purpose: To persuade

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to support increased legal penalties for sex traffickers.

Thesis (Central Idea): Human sex trafficking is a global challenge with local implications, but it can be addressed through multi-pronged efforts from governments and non-profits.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will define and explain the extent of the problem of sex trafficking within our community while examining the effects this has on the victims. Then, I will offer possible solutions to take the predators off the streets and allow the victims to reclaim their lives and autonomy.

- The problem of human sex trafficking is best understood by looking at the severity of the problem, the methods by which traffickers kidnap or lure their victims, and its impact on the victim.

- The problem of human sex trafficking can be solved by working with local law enforcement, changing the laws currently in place for prosecuting the traffickers and pimps, and raising funds to help agencies rescue and restore victims.

Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

To review the problem-solution pattern, recall that the main points do not explain the cause of the problem, and in some cases, the cause is not necessary to explain. For example, in discussing the problem of teenage pregnancy, most audiences will not need to be informed about what causes someone to get pregnant. However, there are topics where discussing the cause is imperative to understanding the solution. The Problem-Cause-Solution organizational pattern adds a main point between the problem and solution by discussing the cause of the problem. In the body of the speech, there will be three main points: the problem, the cause, and finally, the solution. This pattern is also used for speeches dealing with questions of policy. One of the reasons you might consider this pattern is when an audience is not familiar with the cause. For example, if gang activity is on the rise in the community you live in, you might need to explain what causes an individual to join a gang in the first place. By explaining the causes of a problem, an audience might be more likely to accept the solution(s) you’ve proposed. Let’s look at an example of a speech on gangs.

Topic: The Rise of Gangs in Miami-Dade County

General Purpose: To persuade

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to urge their school boards to include gang education in the curriculum.

Thesis (Central Idea): The uptick in gang affiliation and gang violence in Miami-Dade County is problematic, but if we explore the causes of the problem, we can make headway toward solutions.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will explain the growing problem of gang affiliation and violence in Miami-Dade County. Then, I will discuss what causes an individual to join a gang. Finally, I will offer possible solutions to curtail this problem and get gangs off the streets of our community.

- The problem of gang affiliation and violence is growing rapidly, leading to tragic consequences for both gang members and their families.

- The causes of the proliferation of gangs can be best explained by feeling disconnected from others, a need to fit in, and a lack of supervision after school hours.

- The problem of the rise in gangs can be solved, or minimized, by offering after-school programs for youth, education about the consequences of joining a gang, and parent education programs offered at all secondary education levels.

Let’s revisit the human sex trafficking topic from above. Instead of using only a problem-solution pattern, the example that follows adds “cause” to their main points.

Topic: Human Sex Trafficking

General Purpose: To persuade

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to support increased legal penalties for sex traffickers.

Thesis (Central Idea): Human sex trafficking is a global challenge with local implications, but it can be addressed through multi-pronged efforts from governments and non-profits.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will define and explain the extent of the problem of sex trafficking within our community while examining the effects this has on the victims. Second, I will discuss the main causes of the problem. Finally, I will offer possible solutions to take the predators off the streets and allow the victims to reclaim their lives.

- The problem of human sex trafficking is best understood by looking at the severity of the problem, the methods by which traffickers kidnap or lure their victims, and its impact on the victim.

- The cause of the problem can be recognized by the monetary value of sex slavery.

- The problem of human sex trafficking can be solved by working with local law enforcement, changing the current laws for prosecuting traffickers, and raising funds to help agencies rescue and restore victims.

Comparative Advantages

Sometimes your speech will showcase a problem, but there are multiple potential solutions for the audience to consider. In cases like these, the comparative advantages organizational pattern is an appropriate way to structure the speech. This pattern is commonly used when there is a problem, but the audience (or the public) cannot agree on the best solution. When your goal is to convince the audience that your solution is the best among the options, this organizational pattern should be used.

Consider the hot topic of student loan debt cancellation. There is a rather large divide among the public about whether or not student loans should be canceled or forgiven by the federal government. Once again, audience factors come into play as attitudes and values on the topic vary greatly across various political ideologies, age demographics, socioeconomic statuses, educational levels, and more.

Let’s look at how you might organize a speech on this topic. In the body of this speech, one main point is the problem, and the other main points will depend on the number of possible solutions.

Topic: Federal Student Loan Debt Cancellation

General Purpose: To persuade

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to support the government cancellation of $10,000 in federal student loan debt.

Thesis (Central Idea): Student loans are the largest financial hurdle faced by multiple generations, and debt cancellation could provide needed relief to struggling individuals and families.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will define and explain the extent of the student loan debt problem in the United States. Then, I will offer possible solutions and convince you that the best solution is a debt cancellation of $10,000.

- Student loan debt is the second greatest source of financial debt in the United States and several solutions have been proposed to address the problem created by unusually high levels of educational debt.

- The first proposed solution is no debt cancellation. This policy solution would not address the problem.

- The second proposed solution is $10,000 of debt cancellation. This is a moderate cancellation that would alleviate some of the financial burden faced by low-income and middle-class citizens without creating vast government setbacks.

- The third proposed solution is full debt cancellation. While this would help many individuals, the financial setback for the nation would be too grave.

- As you can see, there are many options for addressing the student loan debt problem. However, the best solution is the cancellation of $10,000.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Format

Alan H. Monroe, a Purdue University professor, used the psychology of persuasion to develop an outline for making speeches that will deliver results and wrote about it in his book Monroe’s Principles of Speech (1951). It is now known as Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. This is a well-used and time-proven method to organize persuasive speeches for maximum impact. It is most often used for speeches dealing with questions of policy. You can use it for various situations to create and arrange the components of any persuasive message. The five steps are explained below and should be followed explicitly and in order to have the greatest impact on the audience.

Step One: Attention

In this step, you must get the attention of the audience. The speaker brings attention to the importance of the topic as well as their own credibility and connection to the topic. This step of the sequence should be completed in your introduction like in other speeches you have delivered in class. Review chapter 9 for some commonly used attention-grabber strategies.

Step Two: Need

In this step, you will establish the need; you must define the problem and build a case for its importance. Later in this chapter, you will find that audiences seek logic in their arguments, so the speaker should address the underlying causes and the external effects of a problem. It is important to make the audience see the severity of the problem, and how it affects them, their families, and/or their community. The harm, or problem that needs changing, can be physical, financial, psychological, legal, emotional, educational, social, or a combination thereof. It must be supported by evidence. Ultimately, in this step, you outline and showcase that there is a true problem that needs the audience’s immediate attention. For example, it is not enough to say “pollution is a problem in Florida,” you must demonstrate it with evidence that showcases that pollution is a problem. For example, agricultural runoff is said to cause dangerous algal blooms on Florida’s beaches. You could show this to your audience with research reports, pictures, expert testimony, etc.

Step Three: Satisfaction

In this step, the need must be “satisfied” with a solution. As the speaker, this is when you present the solution and describe it, but you must also defend that it works and will address the causes and symptoms of the problem. Do you recall “need, plan, and practicality”? This step involves the plan and practicality elements. This is not the section where you provide specific steps for the audience to follow. Rather, this is the section where you describe “the business” of the solution. For example, you might want to change the voting age in the United States. You would not explain how to do it here; you would explain the plan –what the new law would be – and its practicality – how that new law satisfies the problem of people not voting. Satisfy the need!

Step Four: Visualization

In this step, your arguments must look to the future either positively or negatively, or both. If positive, the benefits of enacting or choosing your proposed solution are explained. If negative, the disadvantages of not doing anything to solve the problem are explained. The purpose of visualization is to motivate the audience by revealing future benefits or using possible fear appeals by showing future harms if no changes are enacted. Ultimately, the audience must visualize a world where your solution solves the problem. What does this new world look like? If you can help the audience picture their role in this new world, you should be able to get them to act. Describe a future where they fail to act, and the problem persists or is exacerbated. Or, help them visualize a world where their adherence to the steps you outlined in your speech remediates the problem.

Step Five: Action

In the final step of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence, we tell the audience exactly what needs to be done by them. Not a general “we should lower the voting age” statement, but rather, the exact steps for the people sitting in front of you to take. If you really want to move the audience to action, this step should be a full main point within the body of the speech and should outline exactly what you need them to do. It isn’t enough to say “now, go vote!” You need to tell them where to click, who to write, how much to donate, and how to share the information with others in their orbit. In the action step, the goal is to give specific steps for the audience to take, as soon as possible, to move toward solving the problem. So, while the satisfaction step explains the solution overall, the action section gives concrete ways to begin making the solution happen. The more straightforward and concrete you can make the action step, the better. People are more likely to act if they know how accessible the action can be. For example, if you want your audience to be vaccinated against the hepatitis B virus (HBV), you can give them directions to a clinic where vaccinations are offered and the hours of that location. Do not leave anything to chance. Tell them what to do. If you have effectively convinced them of the need/problem, you will get them to act, which is your overall goal.

Claim-to-Proof Pattern

A claim-to-proof pattern provides the audience with reasons to accept your speech proposition (Mudd & Sillars, 1962). State your claim (your thesis) and then prove your point with reasons (main points). The proposition is presented at the beginning of the speech, and in the preview, tells the audience how many reasons will be provided for the claim. Do not reveal too much information until you get to that point in your speech. We all hear stories on the news about someone killed by a handgun, but it is not every day that it affects us directly, or that we know someone who is affected by it. One student told a story of a cousin who was killed in a drive-by shooting, and he was not even a member of a gang.

Here is how the setup for this speech would look:

Thesis and Policy Claim: Handgun ownership in America continues to be a controversial subject, and I believe that private ownership of handguns should have limitations.

Preview: I will provide three reasons why handgun ownership should be limited.

When presenting the reasons for accepting the claim, it is important to consider the use of primacy-recency. If the audience is against your claim, put your most important argument first. For this example, the audience believes in no background checks for gun ownership. As a result, this is how the main points may be written to try and capture the audience who disagrees with your position. We want to get their attention quickly and hold it throughout the speech. You will also need to support these main points. Here is an example:

- The first reason background checks should be mandatory is that when firearms are too easily accessed by criminals, more gun violence occurs.

- A second reason why background checks should be mandatory is that they would lower firearm trafficking.

Moving forward, the speaker would select one or two other reasons to bring into the speech and support them with evidence. The decision on how many main points to have will depend on how much time you have for this speech, and how much research you can find on the topic. If this is a pattern your instructor allows, speak with them about sample outlines. This pattern can be used for fact, value, or policy speeches.

Methods of Persuasion

The three methods of persuasion were first identified by Aristotle, a Greek philosopher in the time of Ancient Greece. In his teachings and book, Rhetoric, he advised that a speaker could persuade their audience using three different methods: Ethos (persuasion through credibility), Pathos (persuasion through emotion), and Logos (persuasion through logic). In fact, he said these are the three methods of persuasion a speaker must rely on.

Figure 10.3: Aristotle3

Ethos

By definition, ethos is the influence of a speaker’s credibility, which includes character, competence, and charisma. Remember in earlier chapters when we learned about credibility? Well, it plays a role here, too. The more credible or believable you are, the stronger your ethos. If you can make an audience see you believe in what you say and have knowledge about what you say, they are more likely to believe you and, therefore, be more persuaded by you. If your arguments are made based on credibility and expertise, then you may be able to change someone’s mind or move them to action. Let’s look at some examples.

If you are considering joining the U.S. Air Force, do you think someone in a military uniform would be more persuasive than someone who was not in uniform? Do you think a firefighter in uniform could get you to make your house more fire-safe than someone who was not in uniform? Their uniform contributes to their ethos. Remember, credibility comes from audience perceptions – how they perceive you as the speaker. You may automatically know they understand fire safety without even opening their mouths to speak. If their arguments are as strong as the uniform, you may have already started putting your fire emergency kit together! Ultimately, we tend to believe in people in powerful positions. We often obey authority figures because that’s what we have been taught to do. In this case, it works to help us persuade an audience.

Advertising campaigns also use ethos well. Think about how many celebrities sell you products. Whose faces do you regularly see? Taylor Swift, Kerry Washington, Kylie Jenner, Jennifer Aniston? Do they pick better cosmetics than the average woman, or are they using their celebrity influence to persuade you to buy? If you walk into a store to purchase makeup and remember which ones are Kylie Jenner’s favorite makeup, are you more likely to purchase it? Pop culture has power, which is why you see so many celebrities selling products on social media. Now, Kylie may not want to join you in class for your speech (sorry!), so you will have to be creative with ethos and incorporate experts through your research and evidence. For example, you need to cite sources if you want people to get a flu shot, using a doctor’s opinion or a nurse’s opinion is critical to get people to make an appointment to get the shot. You might notice that even your doctor shares data from research when discussing your healthcare. Similarly, you have to be credible. You need to become an authority on your topic, show them the evidence, and persuade them using your character and charisma.

Finally, ethos also relates to ethics. The audience needs to trust you and your speech needs to be truthful. Most importantly, this means ethical persuasion occurs through ethical methods – you should not trick your audience into agreeing with you. It also means your own personal involvement is important and the topic should be something you are either personally connected to or passionate about. For example, if you ask the audience to adopt a puppy from a rescue, will your ethos be strong if you bought your puppy from a pet store or breeder? How about asking your audience to donate to a charity; have you supported them yourself? Will the audience want to donate if you haven’t ever donated? How will you prove your support? Think about your own role in the speech while you are also thinking about the evidence you provide.

Pathos

The second appeal you should include in your speech is pathos, an emotional appeal. By definition, pathos appeals evoke strong feelings or emotions like anger, joy, desire, and love. The goal of pathos is to get people to feel something and, therefore, be moved to change their minds or to act. You want your arguments to arouse empathy, sympathy, and/or compassion. So, for persuasive speeches, you can use emotional visual aids or thoughtful stories to get the audience’s attention and hook them in. If you want someone to donate to a local women’s shelter organization to help the women further their education at the local community college, you might share a real story of a woman you met who stayed at the local shelter before earning her degree with the help of the organization. We see a lot of advertisement campaigns rely on this. They show injured military veterans to get you to donate to the Wounded Warriors Project, or they show you injured animals to get you to donate to animal shelters. Are you thinking about how your own topic is emotional yet? We hope so!

In addition, we all know that emotions are complex. So, you can’t just tell a sad story or yell out a bad word to shock them and think they will be persuaded. You must ensure the emotions you engage relate directly to the speech and the audience. Be aware that negative emotions can backfire, so make sure you understand the audience, so you will know what will work best. Don’t just yell at people that they need to brush their teeth for two minutes or show a picture of gross teeth; make them see the benefits of brushing for two minutes by showing beautiful teeth too.

Emotional appeals also need to be ethical and incorporated responsibly. Consider a persuasive speech on distracted driving. If your audience is high school or college students, they may be mature enough to see an emotional video or photo depicting the devastating consequences of distracted driving. If you’re teaching an elementary school class about car safety (e.g., keeping your seatbelt on, not throwing toys, etc.), it would be highly inappropriate to scare them into compliance by showing a devastating video of a car accident. As an ethical public speaker, it is your job to use emotional appeals responsibly.

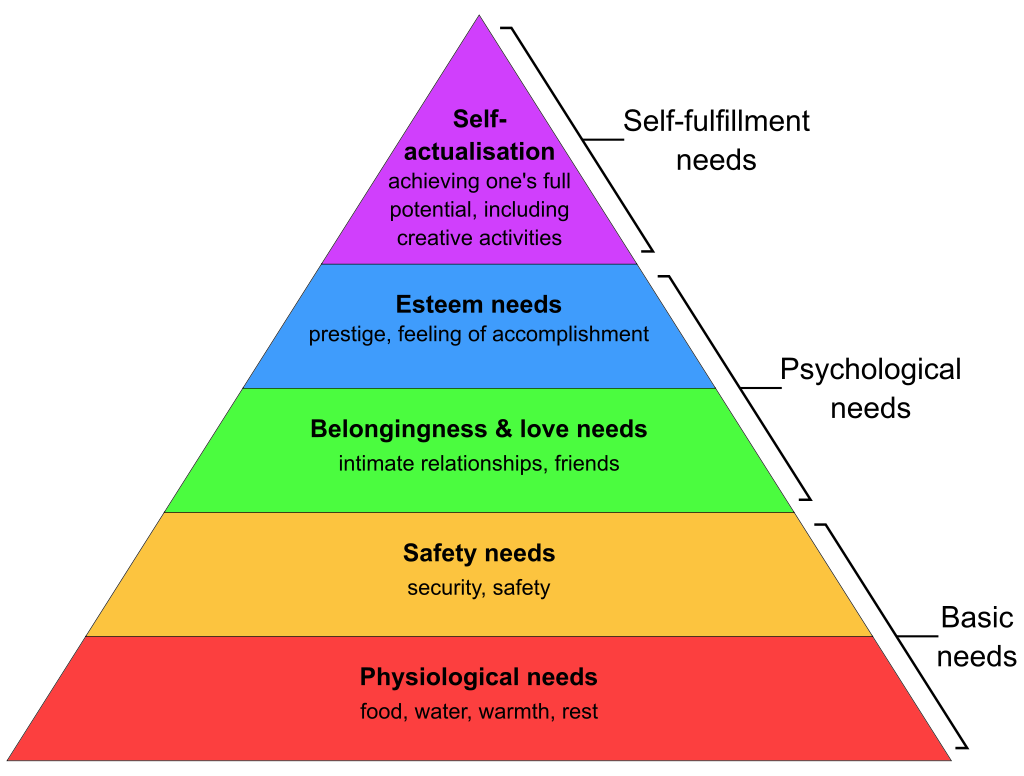

One way to do this is to connect to the theory by Abraham Maslow, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which states that our actions are motivated by basic (physiological and safety), psychological (belongingness, love, and esteem), and self-fulfillment needs (self-actualization). To persuade, we have to connect what we say to the audience’s real lives. Here is a visual of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid:

Figure 10.4: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs4

Notice the pyramid is largest at the base because our basic needs are the first that must be met. Ever been so hungry you can’t think of anything except when and what you will eat? (Hangry anyone?) Well, you can’t easily persuade people if they are only thinking about food. It doesn’t mean you need to bring snacks to your speech class on the day of your speech (albeit, this might be relevant to a food demonstration speech). Can you think about other ways pathos connects to this pyramid? How about safety and security needs, the second level on the hierarchy? Maybe your speech is about persuading people to purchase more car insurance. You might argue they need more insurance so they can feel safer on the road. Or maybe your family should put in a camera doorbell to make sure the home is safe. Are you seeing how we can use arguments that connect to emotions and needs simultaneously?

The third level in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, love and belongingness, is about the need to feel connected to others. This need level is related to the groups of people we spend time with like friends and family. This also relates to the feeling of being “left out” or isolated from others. If we can use arguments that connect us to other humans, emotionally or physically, we will appeal to more of the audience. If your topic is about becoming more involved in the church or temple, you might highlight the social groups one may join if they connect to the church or temple. If your topic is on trying to persuade people to do a walk for charity, you might showcase how doing the event with your friends and family becomes a way of raising money for the charity and carving out time with, or supporting, the people you love. For this need, your pathos will be focused on connection. You want your audience to feel like they belong in order for them to be persuaded. People are more likely to follow through on their commitments if their friends and family do it. We know that if our friends go to the party, we are more likely to go, so we don’t have FOMO (fear of missing out). The same is true for donating money; if your friends have donated to a charity, you might want to be “in” the group, so you would donate also.

Finally, we will end this pathos section with an example that connects Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to pathos. Maybe your speech is to convince people to remove the Instagram app from their phones, so they are less distracted from their life. You could argue staying away from social media means you won’t be threatened online (safety), you will spend more real-time with your friends (belongingness), and you will devote more time to writing your speech outlines (esteem and achievement). Therefore, you can use Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a roadmap for finding key needs that relate to your proposition which helps you incorporate emotional appeals.

Logos

The third and final appeal Aristotle described is logos, which, by definition, is the use of logical and organized arguments that stem from credible evidence supporting your proposition. When the arguments in your speech are based on logic, you are utilizing logos. You need experts in your corner to persuade; you need to provide true, raw evidence for someone to be convinced. You can’t just tell them something is good or bad for them, you have to show it through logic. You might like to buy that product, but how much does it cost? When you provide the dollar amount, you provide some logos for someone to decide if they can and want to purchase that product. How much should I donate to that charity? Provide a dollar amount reasonable for the given audience, and you will more likely persuade them. If you asked a room full of students to donate $500.00 to a charity, it isn’t logical. If you asked them to donate $10.00 instead of buying lattes for two days, you might actually persuade them.

So, it is obvious that sources are a part of logos, but so is your own honest involvement with the topics. If you want people to vote, you need to prove voting matters and make logical appeals to vote. We all know many people say, “my vote doesn’t count.” Your speech needs to logically prove that all votes count, and you need to showcase that you always vote in the local and national elections. In this example, we bring together your ethos and your pathos to sell us on the logos. All three appeals together help you make your case. Audiences are not only persuaded by experts, or by emotions, they want it all to make sense! Don’t make up a story to “make it fit”. Instead, find a real story that is truthful, emotional, and one your audience can relate to make your speech logical from beginning to end and, therefore, persuasive.

Reasoning and Fallacies in Your Speech

In this chapter, we have provided you with several important concepts in the persuasive speech process, including patterns of organization and methods of persuasion. Now, we want to make sure your speech content is clear and includes strong and appropriate arguments. You have done extensive research to support the claims you will make in your speech, but we want to help you ensure that your arguments aren’t flawed. Thus, we will now look at different forms of reasoning and fallacies (or errors) to avoid in your logic.

Reasoning

Thus far, you have read how Aristotle’s proofs can and should be used in a persuasive speech. But, you might wonder how that influences the approach you take in writing your speech outline. You already know your research needs to be credible, and one way to do this is through research. Let’s now put this all together by explaining how reasoning is used in a speech, as well as the fallacies, or errors in reasoning, that often occur when speechwriting.

You may have seen graduation requirements include the category of critical thinking, which is the ability to think about what information you are given and make sense of it to draw conclusions. Today, colleges, universities, and employers are seeking individuals who have these critical thinking skills. Critical thinking can include abilities like problem-solving or decision-making. How did you decide on which college to start your higher educational journey? Was it a decision based on finances, being close to home, or work? This decision involved critical thinking. Even if you had an emotional investment in this decision (pathos), you still needed to use logic, or logos, in your thought process. Reasoning is the process of constructing arguments in a logical way. The use of evidence, also known as data, is what we use to prove our claims. We have two basic and important approaches for how we come to believe something is true. These are known as induction and deduction. Let us explain.

Inductive Reasoning

You have probably used inductive reasoning in your life without even knowing it! Inductive reasoning is a type of reasoning in which examples or specific instances are used to provide strong evidence for (though not absolute proof of) the truth of the conclusion (Garcia, 2022). In other words, you are led to a conclusion through your “proof”. With inductive reasoning, we are exposed to several different examples of a situation, and from those examples, we conclude a general truth because there is no theory to test. Think of it this way: you first make an observation, then, observe a pattern, and finally, develop a theory or general conclusion.

For instance, you visit your local grocery store daily to pick up necessary items. You notice that on Sunday, two weeks ago, all the clerks in the store were wearing football jerseys. Again, last Sunday, the clerks wore their football jerseys. Today, also a Sunday, they’re wearing them again. From just these three observations, you may conclude that on Sundays, these supermarket employees wear football jerseys to support their favorite teams. Can you conclude that this pattern holds indefinitely? Perhaps not; the phenomenon may only take place during football season. Hypotheses typically need much testing before confirmation. However, it seems likely that if you return next Sunday wearing a football jersey, you will fit right in.

In another example, imagine you ate an avocado, and soon afterward, the inside of your mouth swelled. Now imagine a few weeks later you ate another avocado and again the inside of your mouth swelled. The following month, you ate yet another avocado, and you had the same reaction as the last two times. You are aware that swelling on the inside of your mouth can be a sign of an allergy to avocados. Using induction, you conclude, more likely than not, you are allergic to avocados.

Data (evidence): After I ate an avocado, the inside of my mouth was swollen (1st time).

Data (evidence): After I ate an avocado, the inside of my mouth was swollen (2nd time).

Data (evidence): I ate an avocado, and the inside of my mouth was swollen (3rd time).

Additional Information: Swollen lips can be a sign of a food allergy.

Conclusion: Likely, I am allergic to avocados.

Inductive reasoning can never lead to absolute certainty. Instead, induction allows you to say, given the examples provided for support, the conclusion is most likely true. Because of the limitations of inductive reasoning, a conclusion will be more credible if multiple lines of reasoning are presented in its support. This is how inductive reasoning works. Now, let’s examine four common methods of inductive reasoning to help you think critically about your persuasive speech.

Analogies

An analogy allows you to draw conclusions about an object or phenomenon based on similarities to something else (Garcia, 2022). Sometimes the easiest way to understand reasoning is to start with a simple analogy. An avid DIY enthusiast may love to paint -walls, furniture, and objects. To paint well, you need to think about what materials you will need, a knowledge of the specific steps to paint, and the knowledge of how to use an approach to painting so that your paint doesn’t run and your project comes out perfectly! Let’s examine how this example works as an analogy.

Analogies can be figurative or literal. A figurative analogy compares two things that share a common feature, but are still different in many ways. For example, we could say that painting is like baking; they both involve making sure that you have the correct supplies and follow a specific procedure. There are similarities in these features, but there are profound differences. However, a literal analogy is where the two things under comparison have sufficient or significant similarities to be compared fairly (Garcia, 2022). A literal analogy might compare different modalities at the school where your authors teach. If we claim that you should choose Florida SouthWestern State College’s face-to-face courses rather than enrolling in online courses, we could make literal comparisons of the courses offered, available student services, or the classroom atmosphere, for instance.

If we use the more literal analogy of where you choose to go to college, we are using an analogy of two similar “things,” and hopefully, this makes your analogy carry more weight. What this form of reasoning does is lead your audience to a conclusion. When we address fallacies later in this chapter, you will see that comparing two things that are not similar enough could lead you might make an error, or what we call a false analogy fallacy.

Generalization

Another effective form of reasoning is through the use of generalizations. Generalization is a form of inductive reasoning that draws conclusions based on recurring patterns or repeated observations (Garcia, 2022), observing multiple examples and looking for commonalities in those examples to make a broad statement about them. For example, if I tried four different types of keto bread (the new craze), and found that each of them tasted like Styrofoam, I could generalize and say all keto bread is NOT tasty! Or, if in your college experience, you had two professors that you perceived as “bad professors,” you might take a big leap and say that all professors at your campus are “bad.” As you will see later in the discussion on fallacies, this type of reasoning can get us into trouble if we draw a conclusion without sufficient evidence, also known as a hasty generalization. Have you ever drawn a conclusion about a person or group of people after only one or two experiences with them? Have you ever decided you disliked a pizza place because you didn’t like the pizza the first time you tried it? Sometimes, we even do this in our real lives.

Causal Reasoning

Causal reasoning is a form of inductive reasoning that seeks to make cause-effect connections (Garcia, 2022). We don’t typically give this a lot of thought. In the city where one of your authors lives, there are periodic street closures with cones up or signs to redirect drivers. The past several times this has happened, it has been because there was a community 5K run. It is easy to understand why each time I see cones I assume there is a 5K event. However, there could be a completely different cause that I didn’t even think about. The cones could be there due to a major accident or road work.

Reasoning from Sign

Reasoning from sign is a form of inductive reasoning in which conclusions are drawn about phenomena based on events that precede or co-exist with (but do not cause) a subsequent event (Garcia, 2022). In Southern California, a part of the country with some of the worst droughts, one may successfully predict when summer is coming. The lawn begins to die, and the beautiful gardens go limp. All of this occurs before the temperature reaches 113 degrees and before the calendar changes from spring to summer. Based on this observation, there are signs that summer has arrived.

Like many forms of reasoning, it is easy to confuse “reasoning from sign” with “causal reasoning.” Remember, that for this form of reasoning, we looked at an event that preceded another, or co-existed, not an event that occurred later. IF the weather turned to 113 degrees, and then the grass and flowers began to die, then it could be causal.

Deductive Reasoning

The second type of reasoning is known as deductive reasoning, or deduction, which is a conclusion based on the combination of multiple premises that are generally assumed to be true (Garcia, 2022). Whereas with inductive reasoning, we were led to a conclusion, deductive reasoning starts with the overall statement and then identifies examples that support it to reach the conclusion.

Deductive reasoning is built on two statements whose logical relationship should lead to a third statement that is an unquestionably correct conclusion, as in the following example:

Grocery store employees wear football jerseys on Sundays.

Today is Sunday.

Grocery store employees will be wearing football jerseys today.

Suppose the first statement is true (Grocery store employees wear football jerseys on Sundays) and the second statement is true (Today is Sunday). In that case, the conclusion (Grocery store employees will be wearing football jerseys today) is reasonably expected. If a group must have a certain quality, and an individual is a member of that group, then the individual must have that quality.

Unlike inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning allows for certainty as long as certain rules are followed.

Fallacies in Reasoning

As you might recall from our discussion, we alluded to several fallacies. Fallacies are errors in reasoning logic or making a mistake when constructing an inductive or deductive argument. There are dozens of fallacies we could discuss here, but we will highlight those we find to be the most common. Our goal is to help you think through the process of writing your persuasive speech so that it is based on sound reasoning with no fallacies in your arguments.

Table 10.1 describes fifteen fallacies that can be avoided once you understand how to identify them.

Table 10.1: Fallacies

|

Type of Fallacy |

Definition of Fallacy |

Example of Fallacy |

|

Ad Hominem |

Criticizing the person (such as their character or some other attribute) rather than the issue, assumption, or point of view. |

“I could never vote for Donald Trump. His hair looks ridiculous.” “I could never vote for Joe Biden. He’s in his 70’s.” |

|

Appeal to Novelty |

This occurs when we assert that something is superior because it is new. |

“The latest iPhone update is better than any other because it now allows face recognition while wearing a mask.” |

|

Appeal to Tradition |

When we try to legitimize a position based on tradition alone; it’s always been done this way. |

“Public speaking is only proper when a student is at a lectern in a classroom.” |

|

Bandwagon |

Asserting that an argument should be accepted because it is popular and done by others. |

“You should buy stock in Zoom because the stock prices have soared since the pandemic, and everyone is jumping in!” |

|

Circular Reasoning |

Assuming a conclusion in a premise (saying the same thing twice as both the premise and the conclusion). The argument begins with a claim the speaker is trying to conclude with. |

“Of course the use of performance enhancing drugs in sports should be illegal! After all, it’s against the law!” |

|

Either-Or (false dichotomy) |

Provides only two alternatives when more exist. |

“We better eliminate the Social Security system in the United States or our country will go broke.” |

|

False Analogy |

States that since an argument has one thing in common, they will have everything in common. |

“As a student, I should be able to look at my notes when I take exams. After all, my doctor looks at his notes about me every time I go into the office. He isn’t expected to memorize my chart!” |

|

False Cause |

A fallacy that mistakenly assumes that one event causes another, when in fact there are many possible causes. |

“I went out of the house for a walk on my street and didn’t wear my mask, so I contracted COVID-19.” (Maybe you contracted COVID-19 from exposure at a birthday party last week). |

|

Hasty Generalization |

Appealing to a rather small sample or unrepresentative number of cases to prove a larger issue. |

“So far, I’ve met three British people in England, and they all were nice to me, so all people in the U.K. are nice.” |

|

Non-Sequitur |

Occurs when a conclusion does not follow logically from a premise. |

“It’s time to get my nails done. I wonder if my hairstylist is available next week.” “My washing machine is making noise. I better take my car to the shop soon.” |

|

Red Herring |

Introduces irrelevant material into a discussion so that attention is diverted from the real issue; changing the subject or giving an irrelevant response to distract. |

Mom: “You got home really late last night.” You: “Did I tell you I’m getting an A in math?” “How can I support the President’s sanctions against Russia if I don’t like his healthcare policy?” |

|

Slippery Slope |

Assumes consequences for which there is no evidence they will follow an earlier (harmful) act. |

“All types of killing, like premeditated murder, or manslaughter, will become legal if we legalize physician-assisted suicide in all states.” “If we decrease the school budget, all the teachers will quit and our kids won’t be able to go to school.” |

|

Straw Man |

Misrepresents a position so that it can more easily be attacked; distorts the opponent’s argument so that no one could agree with it. |

“People who are not in favor of eliminating aerosol sprays think it’s okay to destroy the environment.” |

|

Sweeping Generalization |

Assuming that a generalization about a class of things/people necessarily applies to everything/person as if there are no exceptions (like stereotyping). |

“Oh, you’re a student. You just want to party all the time and don’t want to work hard.” “I heard you were a football player. Football players never try hard in school.” |

|

Two Wrongs Make a Right |

Argues that it is okay to do something wrong if someone else did something wrong first. |

Julia defends the lie she told her school by saying, “Well, you lied last month when you said you were home with the flu.” |

Conclusion

In this chapter, you can feel confident that you have learned what you need to know to complete an effective persuasive speech. We have defined persuasion, explained speech propositions and patterns, and offered strategies to persuade, including ways to use logic. We also helped you learn more about inductive and deductive reasoning, and all of the various ways these methods help you construct your speeches. Finally, we provided you with the most common fallacies that could trip you up if you aren’t careful. The goal is to be clear, logical, and persuasive! Motivate your audience. Hey, have you been persuaded to start your speech outline yet? We hope so!

Reflection Questions

- What is the difference between propositions of fact, value, and policy?

- How will you determine which pattern of organization to use for your persuasive speech?

- How might you use ethos, pathos, and logos effectively in your speech? How can you write these three proofs into your content?

- What form(s) of reasoning will you use in your speech? How can you ensure you are not using any fallacies?

Key Terms

Ad Hominem

Appeal to Novelty

Appeal to Tradition

Bandwagon

Causal Reasoning

Circular Reasoning

Claim-to-Proof

Comparative Advantages

Critical Thinking

Data

Deductive Reasoning

Either-Or

Emotional Appeal

Ethos

False Analogy

False Cause

Figurative Analogy

Generalization

Hasty Generalization

Inductive Reasoning

Literal Analogy

Logos

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Non-Sequitur

Pathos

Persuasion

Primacy-recency

Problem-Cause-Solution

Problem-Solution

Proposition

Question of Fact

Question of Policy

Question of Value

Reasoning

Reasoning from Sign

Red Herring

Slippery Slope

Straw Man

Sweeping Generalization

Two Wrongs Make a Right

References

Garcia, A. R. (2022). Inductive and Deductive Reasoning. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://englishcomposition.org/advanced-writing/inductive-and-deductive-reasoning/.

Monroe, A. H. (1949). Principles and types of speech. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Company.

Mudd, C. S. & Sillars, M.O. (1962), Speech; content and communication. San Francisco, CA: Chandler Publishing Company.